The Promise of the Transfer Pathway: Opportunity and Challenge for Community College Students Seeking the Baccalaureate Degree

“I think that one of the powerful statements you can make about transfer is that it is a way to keep higher education whole.”

Member of the Commission on Transfer Policy and Practice (2011)

About the Initiative on Transfer Policy and Practice

In partnership with the College Board’s National Office of Community College Initiatives and the Advocacy & Policy Center, the Initiative on Transfer Policy and Practice highlights the pivotal role of the transfer pathway for students — especially those from educationally disadvantaged backgrounds — seeking the baccalaureate degree; convenes two- and four-year institution leaders to identify policies and practices that enhance this century-old pathway; and promotes a national dialogue about the viability and potential of transfer to address the nation’s need for an educated citizenry that encompasses all sectors of American society.

Acknowledgments

Our thanks go to the members of the Commission on Transfer Policy and Practice (see next page) who helped shape and guide this initiative. We are also thankful for the assistance we received from our colleagues at the Institute for Higher Education Policy (Michelle Cooper, Gregory S. Kienzl, Alexis J. Wesaw, and Amal Kumar) whose empirical analyses form the basis of Chapter 3. We would also like to thank the following colleagues who reviewed earlier versions of this manuscript and provided important insights that improved the quality of the final report: Marilyn Cushman, Alan Heaps, Gregory S. Kienzl, James Montoya, Christen Pollock, Tom Rudin, Myra Smith, Anne Sturtevant, and Alicia Zelek. This report benefits greatly from the help of these individuals, but any errors are the responsibility of the authors.

This publication would not have been possible without the generous support of the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation.

About the Authors

Stephen J. Handel is the executive director of the National Office of Community College Initiatives and Higher Education Relationship Development at the College Board.

Ronald A. Williams is vice president of Community College Initiatives in the Advocacy & Policy Center at the College Board.

Commission on Transfer Policy and Practice

George Boggs, Immediate Past President, American Association of Community Colleges, DC

Rita Cepeda, Chancellor, San Jose/Evergreen Community College District, CA

Michelle Cooper, President, Institute for Higher Education Policy, DC

Kevin Dougherty, Associate Professor of Higher Education, Teachers College, Columbia University, NY

Charlene Dukes, President, Prince George’s Community College, MD

Emily Froimson, Vice President, Higher Education Programs, Jack Kent Cooke Foundation, VA

Donna Hamilton, Associate Provost and Dean of Undergraduate Studies, University of Maryland, MD

Allison Jones, Associate Vice President (retired), Student Academic Services, California State University Chancellor’s Office, CA (Senior Fellow with Achieve, Washington, DC)

Gail Mellow, President, LaGuardia Community College, NY

Yvette Mozie Ross, Associate Provost for Enrollment Management, University of Maryland, Baltimore County, MD

Robert Templin, President, Northern Virginia Community College, VA

Toyia K. Younger, Assistant Provost, Towson University, MD

For the College Board

Ronald A. Williams, Vice President, Community College Initiatives, Advocacy & Policy Center, The College Board, DC

Stephen J. Handel, Executive Director, National Office of Community College Initiatives and Higher Education Relationship Development, The College Board, CA

Marilyn Cushman, Executive Assistant, Advocacy & Policy Center, The College Board, DC

Supplemental Reports

(available at http://advocacy.collegeboard.org/admission-completion/community-colleges)

1. Recurring Trends and Persistent Themes: A Brief History of Transfer

by Stephen J. Handel (The College Board)

2. Understanding the Transfer Process: A Report by the Institute for Higher Education

Policy by Gregory S. Kienzl, Alexis J. Wesaw, and Amal Kumar (IHEP)

3. Transfer as Academic Gauntlet:The Student Perspective

by Stephen J. Handel (The College Board)

Foreword

Over seven million students attend credit-bearing programs in community colleges, the largest postsecondary system of education in the U.S. Many of these students attend a community college so that they may prepare themselves to transfer to a four-year college or university and earn a baccalaureate degree. Among new, first-time community college students, the desire to transfer is especially strong. Surveys indicate that as many as eight in 10 want to transfer. Although some dispute the seriousness of these educational intentions, what is not disputed is that among students who say they want to transfer, most do not.

The transfer pathway, an academic avenue of advancement that was the original raison d’être for the establishment of junior, now community, colleges, is over 100 years old. Since 1901, the year marking the establishment of the first community college, the mission of these amazingly flexible and adaptive institutions has grown to include vocational and workforce training, adult education, and a myriad of other unique programs serving their surrounding communities. Similarly, during this same period, four-year colleges and universities expanded enormously to become an educational enterprise that remains the envy of the world.

Unfortunately, the transfer process has not benefitted from the emergence of community colleges and the expansion of four-year institutions. There are exceptions, of course. Numerous two- and four-year institutions around the country have built and nurtured transfer partnerships for decades, serving thousands of students in the process. If we are honest in our assessment, however, transfer is rarely the first thing on the minds of two- and four-year institutional leaders. Over the past century, the topic has captured their interest only intermittently, and largely during periods of economic downturn, political upheaval, or demographic shifts in the population. Moreover, some political pundits and education prognosticators 100 years ago, and even today, say we need fewer students with baccalaureate degrees and more students with jobs. This desire is as understandable as it is beside the point (and one that would be far more persuasive if such leaders also assured us that they were giving their kids the same advice). Despite this, the majority of today’s community college students, much like those of previous generations, say they want to transfer and earn a baccalaureate degree.

More often than not, however, they do not.

This report is an attempt to understand why. The findings within — culled from the minds of some of the best educators and researchers in the business — will not be the last word on the issue. Our hope, however, is that this report will provide the impetus toward a debate about the importance of the transfer pathway in U.S. higher education and the ways in which this avenue to the baccalaureate degree can be improved. This debate must focus on the ways in which two- and four-year institutional colleagues can work effectively to help students onto an academic pathway we offer to them in the name of access and equity; a pathway whose potential has yet to be fully valued and embraced.

Sincerely,

Ronald A. Williams

Vice President

Community College Initiatives

The College Board Advocacy & Policy Center

Stephen J. Handel

Executive Director

National Office of Community College Initiatives & Relationship Development

The College Board

Executive Summary

In 2010, the College Board’s Advocacy & Policy Center, with financial support from the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, initiated a project to identify ways of improving the efficiency of the transfer pathway, a century-old mechanism that provides community college students with an opportunity to earn the baccalaureate degree at four-year institutions. Both organizations understand that the national focus on increasing the number of individuals with credentials and degrees will require that transfer play a significant role, especially given the fact that 47 percent of all undergraduates attend community colleges. Now and into the future, the way in which two- and four-year institutions embrace transfer — or not — will influence the educational fate of thousands of students in the U.S.

To address this issue, College Board staff reviewed research pertaining to transfer, convened the Commission on Transfer Policy, a committee composed of education leaders having special expertise in serving community college transfer students (a committee roster can be found on page 5) to identify significant and emerging trends that influence transfer, and engaged the Institute for Higher Education Policy (IHEP) to address a series of empirical questions raised by the Commission and College Board staff.

This report, as well as several supplemental reports,* describes the transfer process as it is currently applied; identifies major challenges facing policymakers wishing to expand this pipeline; and provides a set of recommendations for states, two- and fouryear institutions, and other entities, including the philanthropic and research communities, that are designed to advance transfer as a more effective pathway to the baccalaureate degree.

Findings

The empirical and policy findings gathered for this initiative suggest the following:

- Transfer continues to be a popular route to the baccalaureate degree, but the transfer rate has not improved despite more students wishing to transfer.

- The transfer process is too complex.

- The effectiveness of statewide articulation policies in boosting transfer has not yet been established empirically, but transparent transfer credit policies remain essential for student success.

- Community colleges and four-year institutions are rarely acknowledged for the work they do on behalf of transfer, and where transfer-related metrics exist, they are often imprecise, inadequate, or misapplied.

- Community colleges and four-year institutions are different academic cultures that create barriers for students already struggling to maneuver through a too-complex system.

- Financial aid policy is an essential element for an effective transfer plan, but it is not often aligned with other initiatives to boost transfer.

- We do not know the capacity of the current transfer system, and this impairs our ability to meet the nation’s college completion agenda.

Recommendations

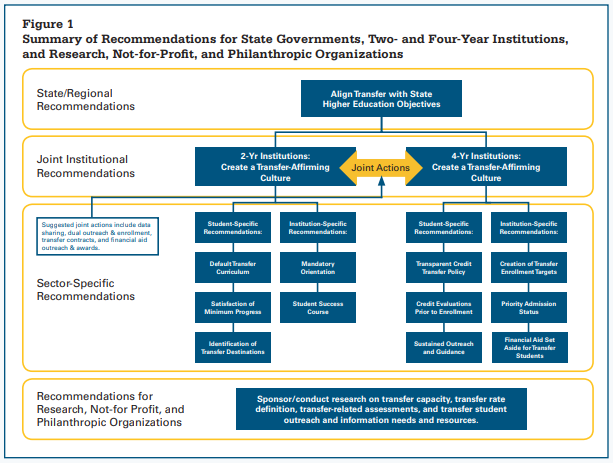

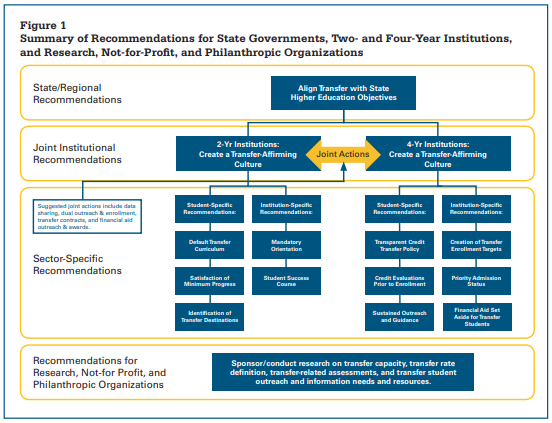

The empirical and policy findings gleaned from this initiative invite the following set of recommendations targeted to state governments, two- and four-year institutions, and the research, policymaking, and philanthropic communities.

- For community college and four-year institution leaders:

Create a transfer-affirming culture that spans your respective campuses, providing a pathway for community college students to advance toward the associate and baccalaureate degrees. Develop partnerships, such as dual admission arrangements or transfer contracts, which provide students with an academic road map. Develop similar partnerships to help students understand their financial aid options. Share information with one another on student goals and intentions, student academic performance, course equivalencies, and changes in programs and requirements with the overarching intention of providing students with a simpler and more coherent transfer process.

- For community college leaders:

Honor and support the intentions of your new, first-time community college students, most of whom overwhelmingly want to earn a four-year degree, by making transfer and the associate degree the default curriculum, unless they opt for a different educational goal. Help students get a good start in higher education by providing them with a mandatory orientation program before their first term in college and/or a student success course in their first term, the product of each being a program of study leading to the associate degree and transfer. Require these students to make at least minimum progress toward their educational goal each term.

- For four-year institution leaders:

Establish an authentic and equal partnership with community colleges focused on transfer. Elevate transfer as a strategic, rather than tactical, objective of your institution’s enrollment plans. Evidence this by insisting that enrollment targets be separate from those developed for freshmen. Share the responsibility of preparing students for transfer by reaching out to community college students in their first year of college with information about academic preparation, financial aid, and credit transfer. Cultivate these students with the same intensity and commitment that you cultivate your high school prospects and demonstrate this commitment by providing them with first-priority in the admission process over other transfer applicants.

- For state government leaders:

Create a coherent transfer strategic plan that aligns with the state’s overall higher education objectives. Incentivize the joint activity of community colleges and four-year institutions to serve community college transfer students, but also hold them accountable with reasonable and meaningful metrics that best assess what each type of institution does best.

- For research, not-for-profit and philanthropic organization leaders:

Develop research methodologies that allow policymakers to assess the capacity of the transfer pathway nationally. Create a definition of transfer that two- and four-year institutions can use to meaningfully assess their progress. Build Web-based college-search and other informational databases for community college students preparing for transfer that are at least as sophisticated as those for high school students applying to college. Develop new evaluation methods that can measure students’ learning outcomes and thereby allow them to demonstrate competency in lieu of completing specific course work that may not have been articulated between any given two- and four-year institutions.

Chapter 1: A Look Forward and a Look Back

“With the current emphasis on the [community] college as the institution which will presumably care for an increasing share of this nation’s college freshmen and sophomores, representatives from all types of four-year colleges and from all types of [community] colleges must use all means of enabling the greatest number of transfer students to have a satisfying and successful experience in the next institution …To date, too much has been left to chance.”

Leland Medsker

This description of the transfer pathway — brief, precise, and instructive — summarizes well the work ahead for educators and policymakers as this nation strives to educate an increasing number of students needing postsecondary credentials and degrees in an intensely competitive and global marketplace.

It was written in 1960.*

The transfer pathway, a century-old mechanism that allows community college students the opportunity to earn a baccalaureate degree, is a shared responsibility of community colleges and four-year colleges and universities. It has not always been viewed that way, however. Even at the beginning of the community college movement in 1901 — a movement initiated by leaders at several of America’s most elite four-year colleges and universities — helping students make the transition from a two-year to a four-year institution was, if not an incidental activity on the part of senior institutions, then certainly a secondary one. Community colleges have also come under similar criticism as these institutions have expanded their mission to include vocational and workforce training, developmental education, and adult education, forcing educators there to balance transfer against a growing list of other priorities. Today, despite the fact that 47 percent of all undergraduate students are enrolled in a community college — and the fact that most new, first-time community college students want to transfer and earn a baccalaureate degree — the relationship between two- and four-year institutions is often strained over disagreements about academic preparation, credit transfer, and control of the baccalaureate degree. As a result, despite this 100-year history, transfer has never been a reliably productive route to the baccalaureate degree. Current estimates indicate that the proportion of community college students who transfer successfully to a four-year institution hovers around 25 to 35 percent, a rate reflecting an enormous opportunity for improvement.

This report highlights the reasons for the sustained neglect of transfer, examines the often ineffectual interactions among two- and four-year institutions that undergird this neglect, and recommends strategies to reverse this outcome. This project was funded by the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation and carried out by the College Board, with the assistance of educators, researchers, and policymakers throughout the United States, all understanding that the way in which two- and four-year institutions embrace transfer — or not — influences the educational fate of tens of thousands of students in the United States.

The release of this report, whatever its shortcomings, could not be more timely. Our nation’s need for a strengthened transfer pathway turns on a number of social and political intersections that are roiling higher education. First, as President Obama made clear in his often quoted 2009 State of the Union address, there is a significant need for more individuals with postsecondary degrees and credentials in the U.S.1 Our increasingly technological economy will require individuals with higher skills so that our workforce can vie effectively with international competitors. Second, gaining ground in an interdependent world economy can only be achieved if we raise the college completion rates substantially among students who have been traditionally underserved in higher education. The gap between rich and poor in this country is at an historic high, and the persistent two-decades-old achievement gap among students from different racial and ethnic groups has been difficult to ameliorate. Third, as the cost of higher education increases, families are looking for ways to cut college costs and minimize debt — especially since the advent of the most recent recession. In the meantime, the public perception of higher education has suffered, threatening the foundation upon which the future of both community colleges and four-year institutions depend. In a recent Pew Center survey, 57 percent of those polled said higher education was doing only a “fair or poor” job of providing “value for money.” The poll went on to note that over two-thirds agreed that access to college, even for those who are qualified, has been compromised (up over 20 percentage points from a similar poll conducted in 2000) (Pew Research Center, 2011, p. 16).

These higher education trends — a need for more degrees, the increasing gap between the haves and the have-nots, and the rising cost of a college degree — are depressingly unassailable, but why do they argue for a strengthened transfer pathway? The most compelling reasons include the following. First, the low cost of community colleges makes these institutions increasingly attractive to all families, even those from upper-income brackets who heretofore never gave these institutions a serious look. They have also attracted the attention of policymakers desperate for ways to educate more students with fewer dollars. Second, two-year institutions are the colleges of choice for students from underserved groups who will constitute the majority of new-student college enrollments in the coming decades. Third, the transfer process has the potential to supply four-year institutions with the student diversity they covet but cannot command via increasingly fragile public support for affirmative action policies. Finally, strengthening transfer simply is the right thing to do. It was a bargain this nation made with community college students a century ago but one that is not yet fulfilled.

* When he wrote The Junior College: Progress and Prospect, Leland Medsker was the vice chair of the Center for Higher Education at the University of California, Berkeley. It is startling to read Medsker’s book today and discover how well his findings anticipate the issues that current policymakers and educators face in helping advance students through the transfer pipeline toward the baccalaureate degree. Medsker’s prescience cuts both ways, however. While acknowledging the depth of his scholarship, Medsker reminds us of how little these issues have advanced in half of a century.

As We Look Forward … A Brief Look Back

Throughout this report we emphasize that the transfer process is a shared responsibility between community colleges and four-year colleges and universities, understanding that both types of institutions are essential in advancing students to the bachelor’s degree (Gandara, Alvarado, Driscoll, & Orfield, 2012, p. 6; Cohen, 2003).2 More often than not, however, transfer — its successes and failures — is associated almost entirely with community colleges. Yet, four-year college and university leaders were instrumental in the establishment of the junior — later community — college and the transfer pathway.3 Their motivations were both pragmatic and self-serving. First, they believed that the creation of two-year institutions would be an effective way of addressing anticipated increases in college enrollment without having these new students overrun their campuses. A second reason was a desire to recast their universities as institutions focused solely on the upper-division curriculum and graduate education, ceding lower-division or general liberal arts education to the two-year institution. In creating this separate institution, four-year institution leaders hoped to “unburden” themselves of the expense and responsibility of offering lower-division courses, while also increasing the selectivity of the students they admitted to the upper division. During the first two decades of community colleges’ history, these four-year college and university leaders, along with local and regional civic leaders, were instrumental in establishing community colleges throughout the country. It has been estimated that state universities were pivotal in the inauguration of 42 percent of all two-year colleges in the U.S. (Dougherty, 1994, p. 142). Moreover, four-year institutions were deeply involved in the development of mechanisms to evaluate and award community college credit so that students could begin their baccalaureate degrees at two-year colleges.4

Although four-year institutions originally believed that their own lower-division curriculum could be addressed by community colleges, the ebb and flow of college enrollments — the lifeblood of any institution, public or private — made it imperative for them to maintain a lower-division curriculum and to continue to admit freshmen. Despite the early and sustained support of four-year institutions, community colleges and four-year institutions — almost from the beginning — were in competition for students, changing the nature of the relationship from one of partner to something approaching a competitor.

It is important to emphasize that transfer was the predominant mission of community colleges from the very beginning. While occupationally oriented programs were available to community college students if they did not move up (or were denied admission to) the senior institution, the proportion of the curriculum devoted to such programs was less than 20 percent (Brint & Karabel, 1989, p. 31; Witt et al., 1995, p. 45). However, as community colleges grew in number throughout the 20th century, the mission of these institutions expanded to include not only a comprehensive lower-division, liberal arts curriculum suitable for preparing students for transfer but also training for a variety of vocational occupations (Levin, 2008).

Community colleges’ expanding vocational mission complicated its relationship with students and intensified an already thorny relationship with four-year institutions. Despite the publicly professed wish of two- and four-year institution leaders that most students entering a community college be counseled to earn a sub-baccalaureate credential, surveys in virtually every decade since the creation of community colleges show that most new, first-time students desire to transfer and earn a four-year degree. Moreover, with an increased focus on occupational training came a perception — accurate or not — that community colleges were less interested in the “higher” portion of higher education; that community colleges had subverted or, at least, weakened their connection with four-year colleges and universities and in doing so undermined the transfer process. In the late 1960s and early 1970s, a period in which the nation opened a new community college every week, the long-simmering debate between two- and four-year institutions intensified about the viability of the transfer process. Researchers noted a decline in the transfer rate, which, despite students’ professed interest, had never been very high (25 to 35 percent of students with transfer intentions — see Chapter 5). Education leaders and policymakers speculated publicly about the causes of this decline, highlighting weakened relationships between two- and four-year institutions and a lack of state policy guidance in making transfer an educational priority.

Quick to defend the role of their institutions in advancing students’ educational progress, community college leaders pointed out that transfer remained an indelible part of their mission, and if there had been any diminution in transfer effectiveness, it was the result of four-year institutions’ lack of interest in community colleges and the students who wished to transfer to their institutions. These leaders pointed to the refusal of four-year institutions to admit more than a handful of their students and four-year institutions’ failure to grant transfer course credit to the ones they did admit.

This interinstitutional debate over transfer, which continues to this day and is one of the reasons this project was commissioned, also highlights a broader uneasiness among most Americans about the essential purpose of a college education. Four-year institutions are seen as providing an education in the liberal arts, a set of skills that their graduates may apply throughout life, regardless of and unsullied by specific career occupational demands. Community colleges, on the other hand, are seen as providing training for the current marketplace. Yet, it would be impossible to argue that four-year institutions are not interested in the employability of their graduates. The establishment of professional schools on their campuses, for example, indicates a willingness to provide occupational training, so long if it is for the “right” kinds of jobs.5 For their part, community colleges, from the very beginning, have offered a lower-division liberal arts curriculum largely mirroring what is offered at four-year institutions. The idea that these institutions are unable to educate students for lifelong learning seems misplaced. Still, it is this tension between what we define as “education” and “training” that plays out uneasily when two- and four-year institutions interact on issues of policy and practice surrounding transfer.

Preview

In the pages that follow, we bring to this century-long debate our own empirical and analytical contributions, with an emphasis on historical and contemporary trends that continue to exert an influence on this academic pathway. For this report, we commissioned a new set of empirical analyses, carried out by researchers at the Institute of Higher Education Policy (IHEP). This report also reflects the guidance of the Commission on Transfer Policy and Practice, a committee convened by the College Board composed of education leaders from around the country possessing both expertise and experience in the area of transfer. In undertaking this work, our overriding goal was to understand better the capacity of the current transfer process to help more students earn the baccalaureate degree; scrutinize transfer from the perspective of students who are asked to navigate this pathway, often on their own and with minimal assistance; and integrate both the policy and empirical research literature in a way that provides higher education leaders with a set of strategies instrumental for improving the transfer process.

The report is organized as follows:

- Chapter 2 addresses current conditions that we believe draw attention to the need for a stronger transfer process. We describe shifts in the American workforce that will require individuals to possess greater levels of knowledge and skill, the pressure of international competition on U.S. economic growth that has highlighted the need for this nation to raise college completion rates, and the necessity of closing the achievement gap for students from underserved groups not only to meet future workforce needs but to fulfill the nation’s democratic ideals.

- Chapter 3 presents the empirical findings from IHEP, which addressed a number of transfer-related questions, including: What are the characteristics of first-time community college students and how do they compare to students who begin college at four-year institutions? What are some of the student-, institutional-, and state-level factors that accelerate or hinder transfer? How do the bachelor’s degree attainment rates of transfer students compare to four-year students who are roughly at the same place in their studies?

- Chapters 4–8 highlight five broad topics on which the improvement of the transfer pathway rests: the capacity of the transfer pathway to accommodate more students; the need to develop appropriate institutional incentives to support transfer, while implementing appropriate accountability metrics to measure progress; identifying and addressing those places in the process where we lose most of our potential transfers; restructuring financial aid to support transfer students; and bridging the academic cultures of two- and four-year institutions.

- Chapters 9 and 10 highlight the major findings from this initiative and delineate a series of recommendations for state governments, two- and four-year institutions, and research and philanthropic organizations.

Finally, we offer three supplemental reports that address, in greater depth, issues touched on in this report. The first focuses on the history of transfer, especially the evolving, sometimes uneasy, relationship between two- and four-year institutions. The second is the technical report showcasing the empirical results described in Chapter 3. The third report is a student-view narrative of the transfer process and its on-the-ground challenges. (Supplemental reports are available at http://advocacy.collegeboard.org/admissioncompletion/community-colleges.)

A Note About Transfer and Student “Swirl”

Our examination of transfer in this report is focused on the traditional two-year to four-year institution pathway, sometimes called “vertical transfer.” We appreciate that many students, indeed the majority of students, do not attend a community college for two years, transfer to a four-year institution, and complete their degree in four years. Even students who first attend a four-year institution rarely finish in the traditional four-year timeframe. Moreover, research indicates that most students who wish to earn a baccalaureate degree may attend several community colleges before they transfer. Most community college students attend on a part-time basis; other students “stop-in” and “stop-out” of these institutions, sometimes completing only one or two courses in a given academic year. Why focus on the “traditional” vertical pathway, especially since it does not mirror the behavior of current community college students? First, vertical transfer, however idealized, represents the historical relationship between community colleges and four-year institutions and remains the most efficient route to the baccalaureate for community college students. Second, despite the variability in students’ academic pathways, we believe that the analyses presented here, along with our policy recommendations, are neither inconsistent with nor antithetical to an understanding of the other transfer pathways that students may follow. Indeed, as our goal is to advance the effectiveness of transfer for all students wishing to earn a four-year degree, efficiencies achieved in the vertical pathway — as it is the most rigorous of transfer scenarios — necessarily aids students following other routes to the baccalaureate degree.

Chapter 2: The Transfer Moment

“A great challenge and an opportunity are at hand … At the very time that global competitiveness depends on a well-educated citizenry, we find ourselves losing ground in relative educational attainment … Between now and 2025, the United States will need to find 15 to 20 million employees, as an aging and highly skilled workforce retires. How is the nation to replace these skills?”

21st Century Commission on the Future of Community Colleges, 2012 (pp. 5–6)

The last 50 years have seen remarkable growth in American higher education (Cohen & Kisker, 2010). Fueled in part by the GI Bill and federal research dollars to maintain this nation’s Cold War readiness, our colleges and universities became (and remain) the envy of the world (Zakaria, 2008). The American community college played a phenomenal part in this growth. Now enshrined in the U.S. higher education landscape, these colleges were imagined by visionary educators at four-year colleges and universities and brought to fruition by junior college — later community college — leaders who correctly saw that this model of higher education access represented a blueprint for the greatest educational experiment of the 20th century. During this period, the United States became the best-educated country in the world.

The new century promises a less optimistic future — unless the nation acts expeditiously. According to the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), the United States ranked sixth among developed nations in the percentage of adults ages 25 to 64 years with an associate degree or higher. Although the United States ranked fourth among developed countries in the postsecondary degree achievements of 55- to 64-year-old adults, our position rank slips to 12th when we look at the academic productivity of 25- to 34-year-olds (OECD, 2008). Moreover, the OECD analyses revealed that the United States ranked near the bottom of industrialized nations in the percentage of students entering college who completed a degree program. The implications, as noted by the Commission on Access, Admissions, and Success in Higher Education, are historic: “We face the prospect that the educational level of one generation of Americans will not exceed, will not equal, perhaps will not even approach, the level of its parents” (College Board, 2008, p. 5).

The uneven productivity of college degrees and credentials comes at a time when the need for highly skilled workers is growing. According to Jobs for the Future, by 2025, the United States must produce 25.1 percent more A.A. degree holders and 19.6 percent B.A. degree holders, over and above current production levels, to meet our nation’s workforce needs (Reindl, 2007). Moreover, to effectively address this degree gap, our nation must increase the number of degrees earned by individuals coming from groups that have been traditionally underrepresented in higher education, including American Indian, African American, Latino, low-income, and first-generation students (NCHEMS, 2007). This disparity in higher education degree productivity for individuals from some underserved groups has been difficult to ameliorate, yet doing so is essential to meet this nation’s need for a better-educated population. This is due to the fact that these groups, especially the Latino population, will increase significantly in the coming decades.

The extent to which other nations have eclipsed the educational productivity of the United States has galvanized the business, policymaking, and philanthropic communities here at home. Still, the most ambitious challenge has come from the federal government. Not since the passage of the GI Bill has a presidential administration placed such emphasis on higher education and pledged the support to provide opportunity to a greater number of students, although this has not translated into funding for direct support of transfer (Goldrick-Rab, Harris, Mazzeo, & Kienzl, 2009, p. 6). During his 2009 State of the Union address, President Obama challenged every American “to commit to at least one year or more of higher education or career training” and challenged this nation to attain the highest proportion of college graduates in the world by 2020.

The need to increase educational productivity in this country raises questions not only about our will to fulfill President Obama’s ambitious goal but whether we have the capacity to do so. It is clear that community colleges will need to be a significant part in meeting any college completion goal, given the number of undergraduates these institutions educate each year.6

Moreover, although the discussion around college completion focuses on increasing the number of people with certificates and degrees of all types, more recent analyses portend an especially urgent need to increase the number of bachelor’s degree holders. Georgetown researchers Anthony P. Carnevale and Stephen J. Rose in their report, The Undereducated American, conclude that the United States will need an additional 20 million postsecondary-educated workers in the next 15 years. Of these 20 million individuals, at least 15 million will need to earn bachelor’s degrees.

Carnevale and Rose argue that such growth, 2 percent per year for the next decade and a half, is needed not only to fill job requirements in the U.S. but also to stem the widening earnings gap between those individuals who possess a high school diploma compared to those who hold a four-year degree. At the current rate of degree production, the income gap is expected to grow, say Carnevale and Rose, to an astonishing 96 percent by 2025 (Carnevale & Rose, 2011).

Carnevale and Rose never mention community colleges or transfer students in their report. Nonetheless, they do stress that increasing “the number of college graduates must be based … on removing barriers to degree completion for qualified students” (p. 32). Surely, creating a smoother transfer pathway falls within this criterion. They also recommend that we improve the quality of our graduating high school seniors. Better-prepared students entering college, whether a two- or four-year institution, are more likely to complete a certificate or degree. But generating 15 million more B.A. degree holders in eight years is so ambitious that, barring an historic and unrealistic turnaround of the K–12 system, it is unlikely that Carnevale and Rose’s goal can be met without relying on the accessibility and capacity of community colleges and the transfer pathway.

There are other reasons why we need a strengthened transfer pathway:

- Community college students want to transfer. Transfer has been and continues to be a popular goal for a large proportion of incoming community college students. Surveys indicate that at least 50 percent and perhaps as many as 80 percent of all incoming (first-time) community college students seek to transfer and earn a bachelor’s degree (Horn, 2009, pp. 8–9; Horn & Skomsvold, 2011, Table 1-A; Provasnik & Planty, 2008, p. 21). Students’ desire to earn a baccalaureate degree has steadily increased since 1989-90 regardless of their racial/ethnic background, age, and income level (see Table 1). Moreover, although students’ educational intentions are often seen as unreliable, the high proportion of entering community college students wishing to transfer has been constant through the history of community colleges (Brint & Karabel, 1989; Medsker, 1960).7 Finally, research has established that many students who intend to earn sub-baccalaureate credentials at a community college often increase their educational aspirations after starting at a two-year college (Rosenbaum, Deil-Amen, & Person, 2006).

- Community colleges are the largest postsecondary education segment, and their share of the undergraduate population is likely to increase. Community colleges enroll more than seven million for-credit students, constituting 47 percent of all undergraduates in the United States (Chronicle of Higher Education, 2012; American Association of Community Colleges [AACC], 2012, p. 8). Moreover, student enrollment in public two-year community colleges dwarfs enrollments in all other sectors of undergraduate higher education (see Table 2). Community college enrollments, especially during the most recent recession, were far more volatile than four-year institution enrollments; nevertheless, community college enrollment increased 9 percent since 2006 (Dadashova, Hossler, Shapiro, Chen, Martin, Torres, Zerquera, & Ziskin, 2011, p. 17). Moreover, the U.S. Department of Education predicts that postsecondary enrollments will grow 13 percent between now and 2020, despite the fact that the national high school graduation rate is predicted to decline 3 percent during the same period. Part of the projected growth in the college-going population will be made up of Latino students, students ages 25–34 years old, and part-time students. These groups are far more likely to attend a community college than a four-year institution (Hussar & Bailey, 2011, pp. 19–24).

- The college-going population is changing. As described in Chapter 1, four-year colleges and universities have historically preferred to enroll students directly from high school rather than community colleges, believing that the supply of first-time students was inexhaustible. But the supply, if not drying up, is certainly slowing down. As noted above, the U.S. Department of Education predicts that the high school graduation rate will be in decline between now and 2020. In 27 states, the Department predicts high school graduation rates will level off or decline (Hussar & Bailey, 2011, p. 10). Thus, certainly in the near term, transfer students will allow four-year institutions to fill seats that would have otherwise been occupied by 18-year-olds.

- Community colleges attract students from underserved groups in significant numbers. White students constitute the majority of community college enrollments as they do four-year institutions. Community colleges, however, enroll significant numbers of African American, Latino, and first-generation students, as well as students from the lowest income level and single-parent families (AACC, 2012; Western Interstate Commission on Higher Education [WICHE], 2008).8 These numbers are likely to increase because, for example, the population of students from underrepresented ethnic groups is expected to increase substantially in the coming decades. Moreover, students from underserved groups, especially Latino and American Indian students, have traditionally enrolled in community colleges in greater numbers than in public four-year institutions, regardless of their income level.9

- Increasing stratification of higher education makes transfer the most important — and perhaps the only — viable avenue for students from underserved groups. The fact that students from underserved groups enroll in community colleges in significant numbers may have more to do with economics than institutional preference. Between 1994 and 2006, the share of African American students enrolling in community colleges increased from 10 percent to 14 percent, and the share of Latino students enrolling in community colleges increased from 11 percent to 19 percent. During the same period, both populations did not increase their share of participation in competitive four-year colleges and universities, despite increases in their respective high school graduation rates (Carnevale & Strohl, 2010, pp. 131–135). As noted earlier, this same pattern is seen in the enrollment of students from the lowest socioeconomic groups, who now make up the majority of enrollments in community colleges. These institutions are the gateway for students from a variety of groups that have been — and continue to be — underrepresented in higher education. That community colleges welcome these nontraditional groups of students is well known. Yet the growing numbers of these students who begin at a community college, coupled with the nation’s need to produce more degree holders, makes the transfer process critically important.

- Community colleges will prepare more students for transfer from traditional backgrounds. There is evidence that traditional student populations are enrolling in community colleges in greater numbers than ever before. The College Board (Baum, Ma, & Payea, 2012, p. 1) reports that students attending community colleges on a full-time basis increased almost 50 percent in the last decade. Moreover, the National Student Clearinghouse Research Center (Dadashova et al., 2011) found as a result of the most recent recession, that “community colleges saw increases in full-time enrollments — suggesting the possibility that students who might otherwise have attended four-year institutions full-time were instead enrolling in greater numbers at community colleges” (Dadashova et al., 2011, p. 46). Other researchers have suggested a similar trend within community colleges (Mullin & Phillippe, 2009; Rhoades, 2012; Bailey & Morest, 2006, p. 5). Such students attending full time are far more likely than other students to have transfer and a bachelor’s degree as a goal. In addition, in a recent survey focusing on how families pay for college, there was a significant shift in the number of high-income families (over $100,000 per year) sending their children to community colleges, increasing from 12 percent in 2009-10 to 22 percent in 2010-11. A similar, though smaller, increase was noted among middle-income families (from 24 percent to 29 percent) (Sallie Mae, 2012, p. 12).

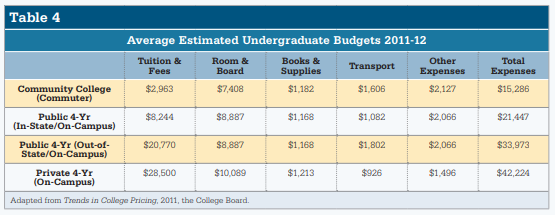

- Community colleges cost less to attend than four-year institutions. As the national debate about college costs intensifies, the relative affordability of community colleges makes these institutions an increasingly attractive option for many American households. Although community college costs are also rising, these institutions remain the most affordable higher education option in the U.S. According to data compiled by AACC, tuition and fees at community colleges average only 36.2 percent of the average fouryear public college tuition and fee bill (AACC, 2009).10 The relative affordability of community colleges is reflected in the number of students from lower socioeconomic levels who attend these institutions. In 2006, over 58 percent of all students attending community colleges came from the lowest two income quartiles and over onequarter (28 percent) came from the lowest income quartile (Carnevale & Strohl, 2010, p. 137).

- Community colleges are more accessible than four-year institutions. Closely linked to the issue of cost, there is a community college located within driving distance of most Americans. Moreover, community colleges are geographically more widely distributed than four-year institutions (Provasnik & Planty, 2008, p. 4, Figure 3). Students rank geographic convenience among the most important reasons for attending a particular college or university.

Highlighting this confluence of variables, a Brookings Institution study recently concluded:

“Confronted with high tuition costs [at four-year institutions], a weak economy, and increased competition for admission to four-year colleges, students today are more likely than at any other point in history to choose to attend a community college” [emphasis added] (GoldrickRab, Harris, Mazzeo, & Kienzl, 2009, p. 10).

The need for a better-educated workforce, the centrality of community colleges as an avenue of higher education access for millions of students from under-served groups, and the untested potential of the transfer process as an expressway to the baccalaureate degree, make this an especially opportune time to assess the strength and efficiency of the community college — four-year institution partnership.

Chapter 3: Empirical Snapshot for the New Century: Transfer Student Gains and Losses

In 2010, the College Board engaged the Institute for Higher Education Policy (IHEP) to tackle the transfer and degree completion research issues identified by the Commission on Transfer Policy and Practice and to supplement these analyses with site visits to two- and four-year institutions. As part of its efforts, IHEP analyzed the latest longitudinal data from the U.S. Department of Education databases focusing on transfer and B.A. attainment rates. In addition, promising practices in transfer policy were investigated based on site visits in several states. The empirical analyses focused on three questions:

- What are the characteristics of first-time community college students and how do they compare to starting students at four-year institutions?

- What are some of the student-, institutional-, and state-level factors that accelerate or hinder transfer?

- How do the bachelor’s degree attainment rates of transfer students compare to four-year students who are roughly at the same place in their studies?

The Complete Picture

The findings presented in this chapter are taken from Understanding the Transfer Process: A Report by the Institute for Higher Education Policy, which was written by Gregory Kienzl, Alexis Wesaw, and Amal Kumar and commissioned specifically for this initiative. A complete description of the data sources, methodology, and findings can be found at:

http://advocacy.collegeboard.org/admissioncompletion/community-colleges

Embedded in these questions are issues such as students’ intentions to transfer, the influence of statewide articulation agreements in encouraging the movement between two- and four-year institutions with minimal burden or loss of momentum, and whether having an associate degree prior to transferring provides the necessary push toward a bachelor’s degree.

Data Sources and Methodology

The study draws from a number of data sources, including the two most recent national longitudinal datasets of first-time college students, characteristics of state transfer and articulation environments, and several campus interviews. The analysis includes both descriptive comparisons as well as multivariate models that attempt to tease out the relationships among key indicators identified in the literature. The findings discussed in this report were based on data drawn from several primary and secondary sources, including the Beginning Postsecondary Students Longitudinal Study (BPS 96-01 and BPS 4/09), the Integrated Postsecondary Education Data System (IPEDS), U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS), the Education Commission of the States’ policy brief on transfer and articulation, and interviews with transfer counselors at five postsecondary institutions in three states.

Results

- Community college students are a diverse population. First-time students attending community colleges are different from firsttime students attending four-year colleges and universities. Community college students are more likely to be older. Forty-four percent of community college students are 20 years of age or older, compared to 14 percent of students attending four-year colleges and universities. Nevertheless, community colleges enroll a sizeable number of students from the traditional 18- to 23-year-old college-going cohort. In this analysis, over 72 percent of first-time community college students are in this age-group, compared to 91 percent for four-year colleges and universities.

Compared to students who begin at a four-year college or university, first-time community college students are also more likely to come from groups that have been traditionally underrepresented in higher education. Although white students comprise about 60 percent of community college enrollments (as compared to 68 percent in four-year institutions), community colleges enroll more first-time African American students (14 percent versus 11 percent at four-year institutions) and Latino students (16 percent versus 10 percent at four-year institutions).

First-time community college students are more likely to come from the lowest income quartile. In this analysis, 26 percent of community college students come from the lowest income quartile, compared to 20 percent for students enrolled in four-year colleges and universities. In addition, first-time community college students who are African American and Latino are more likely to come from the lowest income quartile, compared to white students. Forty-four percent of first-time African American community college students and 35 percent of Latino students are from the lowest income quartile, compared to 18 percent for white students.

Finally, first-time community college students are more likely to have completed at least one remedial course compared to their peers at four-year colleges and universities (30 percent versus 18 percent) and are much less likely to attend college on a full-time basis (49 percent versus 88 percent).

The results of this analysis demonstrate that students attending a community college represent a broad range of backgrounds and personal characteristics. In comparison with four-year colleges and universities, community colleges attract a far more diverse student body in such areas as age, race/ethnicity, income level, and academic preparation.

- The transfer rate remains steady, but more students transfer. In calculating a national transfer rate, a commonly used definition of a transfer student, developed by the Center for the Study of Community Colleges, was used: “A student who started her postsecondary education at a public two-year institution and stayed there at least one full-time semester is considered to have transferred if at any point she was observed at a four-year institution of any type, anywhere for at least one full-time semester.”

From this definition the national transfer rate of community college students who first enrolled in the 2003-04 academic year was calculated as 26 percent. This transfer estimate is statistically indistinguishable from eight years earlier, which was calculated as 27 percent.

Although the transfer rate has remained the same, due to 100,000 more first-time community college students enrolled in postsecondary education now than eight years ago, there has been a net gain of approximately 24,000 transfer students between 1996–2001 and 2004–2009.

- The transfer rate for African American students increased, but the transfer rate for Latino students did not improve. The transfer rate for African American students is 25 percent. Although this transfer rate is similar to the transfer rate for all students, it represents an increase of 9 percentage points over the previous cohort (1996–2001). This increase was especially pronounced for African American students in the lowest- and middle-income quartiles, in which the rate surged 10 and 13 percentage points, respectively, compared to the previous cohort. The transfer rate among African Americans in the highest income quartile, however, dropped 4.5 percentage points — from 24 to 20 percent — over the eight-year period.

The transfer rate for Latino students is 20 percent. Although this rate did not decline substantially from the rate calculated for the previous cohort (less than 1 percent), Latinos have the lowest rate among all students in the current cohort. The transfer rate for Latino students is 8 percent lower than the rate calculated for white transfer students and 6 percent lower than the rate calculated for African American transfer students.

- Student transfer intentions increased but not the number of students that successfully transferred. In spite of a transfer rate that is virtually unchanged from the earlier cohort, a larger proportion of community college students in the current cohort indicated a desire to transfer and earn a bachelor’s degree. In the 1995-96 academic year, 44 percent of the first-time community colleges student population indicated a desire to transfer and earn the baccalaureate degree. In the 2003-04 academic year, this figure was 60 percent.

Unfortunately, although more students intended to transfer and earn a bachelor’s degree in the current cohort, they were less successful in doing so compared to the earlier cohort. Although 60 percent of first-time community college students intended to transfer and earn a bachelor’s degree in the 2004-09 cohort, only 36 percent of these students were successful in doing so. In the 1996– 2001 cohort, 44 percent of first-time community college students intended to transfer and earn a four-year degree and an equal percentage (44 percent) were successful.

- No support for statewide articulation policies on transfer rates was found. Statewide articulation agreements, which require the transfer of lower-division course credit from public community colleges to public four-year colleges and universities, show no statistically significant impact on transfer rates. Although such agreements are designed to assist students by streamlining the transfer process, data indicate a negative correlation between states that have implemented such agreements and the overall transfer rate.

Anecdotal evidence from interviews with transfer coordinators suggests that institution-to-institution articulation agreements have more impact on student transfer rates than statewide policies. Institutional agreements between and among public colleges and universities, while far less comprehensive than statewide agreements (which generally cover entire lower-division programs, such as general education curricula and/or major programs), may be seen by students as perhaps more relevant for their needs, especially because these agreements cover specific courses between only two institutions.

Despite transfer coordinators’ preference for institution-specific agreements over statewide agreements, such agreements are not a perfect solution. Interviews with transfer counselors in two- and four-year institutions in Illinois and Indiana revealed that institution-specific agreements, created by individual college partnerships, usually only cover a single program area or major. They typically allow for block transfer of credit, but only if students transfer to the specific partnership institution. Such agreements are widely seen — at least by these interviewees — as problematic, because they are very specific, limit students’ choices, and can be confusing. To meet the requirements of an agreement, students need to select both a major and a transfer institution, which means that they must engage in detailed planning early in their college careers.

- Institution-based strategies to increase transfer may boost transfer. Interviews conducted with transfer counselors at Portland Community College and Portland State University in Oregon revealed a successful institution-based strategy to ease transfer. In this program, qualified students are co-admitted at both institutions. Participating students have access to many facilities and support services at each institution. Students pay community college tuition for community college courses, and four-year tuition for courses offered through the university.

This program and others like it help transfer students gain access to the receiving institution early in their collegiate career and make transfer a key component of the culture on both campuses. But it also requires significant resources. C-oadmitted students are given multiple forms of support before, during, and after the transfer process, but this support is dependent upon having dedicated transfer staff available to them.

A particular challenge is reaching out to all of the potential transfer students who are not aware of the program and, because they self-advise, do not necessarily see themselves as benefiting from participation. In Oregon, the co-enrollment program is struggling to meet demand. Portland State University is having difficulty serving the large numbers of freshmen and sophomores enrolled or co-enrolled in that institution. This is particularly challenging given the budget cuts facing the institution and higher education generally.

- Bachelor’s degree attainment lags for transfer students compared to their four-year institution peers. Although student success in making the transition from a community college to a four-year institution is an achievement all its own, the ultimate goal is a bachelor’s degree. To what extent do these students succeed in earning this degree compared to their peers who began college at a four-year institution and who have achieved the same level of academic advancement?

To make this comparison, students who successfully transferred from a community college to a four-year institution were compared with students who initiated their college careers at a four-year institution and who achieved junior standing (called “rising juniors”). Comparing successful transfers to rising juniors (rather than the entire cohort of students who began college at the four-year institution) accounts, to some degree, for student attrition that inevitably occurs in both sets of cohorts.

With this analytical framework in mind, community college students do not earn bachelor’s degrees at comparable rates as students who begin at a four-year college or university in the current cohort. Nearly 70 percent of rising juniors earned a bachelor’s degree at four-year colleges and universities, but only 45 percent of transfer students who were seeking a bachelor’s degree had a similar outcome after six years. This gap is sometimes referred to as the “transfer penalty.”11 It is important to stress, however, that about 20 percent of transfer students were still enrolled six years after their initial enrollment in postsecondary education. If the timeline of the study were extended, the difference in attainment rates would shrink considerably.

Limitations of the Analysis

There are two key limitations of the current study. The most critical limitation is a measure of student financial aid. Because data on the type and amount of financial aid offered to a potential transfer student were not gathered in this analysis, modeling the impact of financial aid — separate from students’ personal or family income — in any meaningful way was rendered impossible. Another limitation has been the sole focus on the “supply side” of transfer. Does every eligible community college student have a place for them at a four-year college or university? Additional information would be necessary to address this key aspect of the transfer puzzle.

Do Community College Students Succeed at Four-Year Institutions?

Our results found a difference in graduation rates for students who attend a community college compared to students who begin at a four-year institution. A student who starts at a community college is less likely to earn a baccalaureate degree in six years. Unfortunately, this finding has been replicated numerous times (although, as we note, community college students are sometimes not tracked for a sufficient number of terms to measure success). Of course, that’s part of the reason why this project was initiated: To discover ways of improving the transfer pathway so that many more students transfer and graduate with a four-year degree. What we also found, however, was that students who successfully transferred to a four-year institution were less likely to graduate compared to a matched set of four-year institution peers (that is, students who started at a four-year institution and who also achieved junior status). This finding, however, is far from definitive. Other researchers have discovered just the opposite; that community college students who transfer are as academically successful — if not more so — than students who began at a four-year institution. More research is needed to clear this up. (See Note 11 for additional information and research references.)

Interlude: Challenges to the Expansion of the Transfer Pathway

“Believe it or not, even with the spotlight on community colleges [and the college completion agenda], there are still states … where students are not able to transfer at the junior level even after completing two years at a community college … This is a ridiculous conversation at this point … We’ve got to take that barrier down.”

Walter Bumphus, President,

American Association of Community Colleges, 2010

The findings highlighted in the last chapter show a transfer pathway in distress. Positive findings, such as an increase in the transfer rate for African American students compared to a similar cohort of students assessed eight years earlier, were more than offset by other findings that revealed a stagnate transfer rate for Latino students, no support for statewide articulation agreements in boosting transfer, fewer students who intended to transfer who were successfully in doing so, and the presence of a transfer penalty in the baccalaureate completion rates of students who begin at a community college compared to those who began at a four-year institution.

In the chapters that follow, we draw a crosswalk between those findings and the work of the Commission on Transfer Policy and Practice, which was charged with identifying the most significant barriers in expanding the transfer pathway and to develop recommendations to improve its efficiency. The Commission used two strategies. The first strategy focused on a description of the transfer process as viewed by community college students. The results of this analysis are presented in Supplemental Report 3 Transfer as Academic Gauntlet: The Student Perspective.* The Commission’s second strategy was to identify the most important challenges facing policymakers who wish to enhance the transfer process, guided not only by the empirical data compiled for this project but relying also on the research literature more generally. The Commission identified the following five challenges, which are described in Chapters 4–8:

- Unknown capacity of the transfer pathway to accommodate more students;

- Lack of institutional incentives to support transfer;

- Ruptures in the transfer pipeline where most potential transfers are lost;

- Discontinuities in financial aid that do not support transfer students; and

- Distinct and sometimes contrary academic cultures of two- and four-year institutions that compromise transfer student progress.

Chapter 4: Transfer Capacity: Black Box or Black Hole?

“While community colleges have a critical role to play in preparing some students with important vocational skills, federal education survey data show that 81.4 percent of students entering community college for the first time say they eventually want to transfer and earn at least a bachelor’s degree. That only 11.6 percent of entering community-college students do so within six years is a national tragedy. Some look at these numbers and suggest community colleges should downplay the idea of transfer, but it makes more sense to improve and strengthen transfer paths.”

Richard Kahlenberg (2012)

How many community college students are preparing for transfer nationally? How many of these students make a successful transition to a four-year institution? How many more can the nation’s community colleges and four-year institutions absorb in the coming years to meet our need for students with baccalaureate degrees? Answers to these questions are essential if we wish to boost transfer in substantive ways. Three findings from the empirical analyses described in Chapter 3 are especially relevant to this discussion:

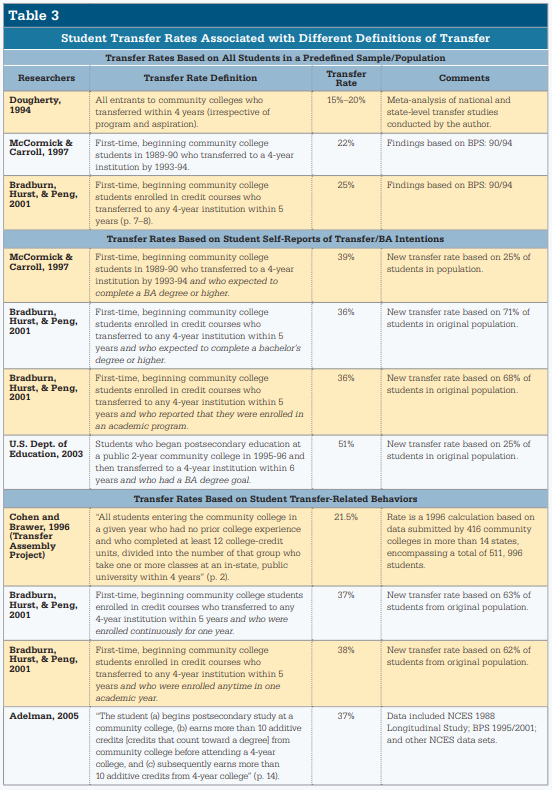

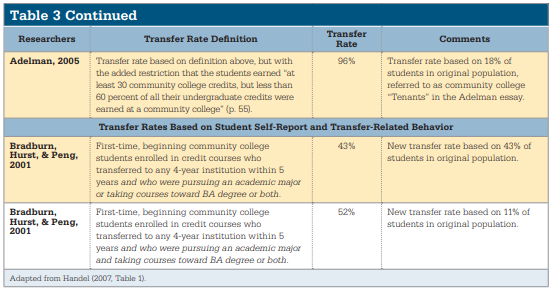

- The transfer rate for first-time community college students is 26 percent, which is consistent with the rate calculated for a similar cohort of students eight years earlier. Although the current findings (and earlier ones) are disheartening, they are not surprising. Similar transfer rate results have been documented for decades by different researchers, using different methodologies, with different populations, and in different regions of the country.

- Although a greater proportion of students in the current cohort intended to transfer and earn a baccalaureate degree, a smaller proportion was actually successful in doing so compared to the earlier cohort of students. While the variability of student intentions is well known, when goals are unrealized — regardless of whether we judge them as realistic or not — it undercuts the equity and access dimension of community colleges that is so universally praised.

- There is a gap in bachelor’s degree attainment for students who transfer from a community college compared to those who begin at a four-year institution. Although our analysis tracked students for only six years, almost certainly not long enough to capture all transfers in the pipeline, the presence of a transfer penalty has been noted by other researchers.

A transfer rate that has not budged in a decade; an increased number of students who want to transfer but, for whatever reason, are unable to do so; and the persistence of a transfer penalty all speak to systemic misalignment within the transfer process. These findings also raise a number of questions about the capacity of the nation to educate more students for the baccalaureate degree using the transfer pathway.

- Does the static transfer rate over the past decade indicate that the nation has reached a ceiling in accommodating students who wish to enter a four-year institution and earn the baccalaureate degree? If such a ceiling exists, what are the causes?

Evidence for an explicit transfer ceiling are indirect and speculative, but intriguing. First, the steadily increasing number of community colleges granting the baccalaureate degree (48 public colleges in 17 states) indicates that four-year institutions alone, at least in some states, are unable to meet transfer student demand (AACC, 2012; Lewin, 2009). Although there are multiple motivations for the push to confer baccalaureate degrees at community colleges, this trend signals that four-year institutions are struggling in addressing the demand for baccalaureate degree holders in high-need fields like nursing and teaching. Second, greater pressure on four-year colleges and universities to retain and graduate their native students, as a result of the national focus on college completion, may mean fewer seats for community college transfer students at these institutions.

- To what extent are four-year colleges and universities anticipating more transfer students coming to their doors, especially given the increase in community college enrollments nationally?

In an informal review of the strategic plans of 15 four-year colleges and universities in states having a strong community college system, we found explicit intentions on the part of these institutions to make transfer students a more important part of their enrollment planning. Two-thirds of the plans highlight the importance of developing stronger relationships with local community colleges, which, if successful, would presumably lead to the enrollment of more transfer students. Only one plan, however, explicitly indicated that the institution planned to expand its enrollment of community college students by decreasing its enrollment target for first-year students.

- What is the relationship between enrollment demand and public resources that are available to accommodate increased demand?

It is no secret that severe budget cuts in response to the last recession have weakened the ability of community colleges and four-year institutions to meet student enrollment demand. The American Association of State Colleges and Universities (AASCU) reports that 11 states in 2010-11 capped enrollment at their public four-year institutions. In addition, seven states limited enrollment at public regional institutions. These enrollment caps occurred in some of the nation’s most populous states (AASCU, 2011, p. 4). Community college enrollments are also being cut or capped. In California for instance, community college officials estimate that 400,000 students were closed out of classes last year, while the California State University reduced transfer student enrollment by 12,000 students across the system in 2010-11 (Associated Press, 2011, p. 3). In response to these dramatic decreases in state support, public four-year institutions in particular have begun to alter their recruitment strategies by focusing on the admission of “full-pay” students to cover losses in appropriations from state governments. While such actions do not preclude the admission of community college transfers, domestic community college students are more likely to come from lower-socioeconomic backgrounds and so may suffer in this competition for seats.

Research also suggests that college completion rates are likely to be negatively impacted unless state and federal support for higher education is increased (Bound & Turner, 2007). Predictions that current levels of austerity will continue for the foreseeable future do not bode well for boosting college completion. Moreover, some data suggest that students who are crowded out of four-year colleges and universities and, as a result, attend a community college, are more likely to earn an associate degree rather than a baccalaureate (Maghakian, n.d.). This suggests that the transfer connection between two- and four-year institutions remains problematic not only for students who begin at a community college but also for those students who initially planned to attend a four-year institution and for whatever reason, chose a community college.

- Are community college students preparing for transfer majors that are already at capacity?

Has the national push to increase the number of students in science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM) majors, for example, overwhelmed the ability of four-year institutions to accommodate demand for these relatively more expensive majors? Are there fewer transfer students majoring in STEM disciplines because of the sequential, often lockstep, nature of such majors? What incentives are in place (or should be) for four-year institutions to help make prospective transfer students “major ready”?

- Does the fact that fewer students with transfer intentions were successful in enrolling at a fouryear institution, as compared to a similar group of students surveyed a decade earlier, imply that there is a problem with transfer advising at the two- and/or four-year institutions?

The data so far examined — along with the historical record — reveal a mismatch between student intentions to transfer and the number that successfully do so. Laying such sustained failure, however, at the feet of guidance counselors is misplaced, although the lack of guidance overall — since academic advising is so often the first to be cut in state budget reductions — may well be one of the culprits. The complexity of the current transfer system (discussed in Chapter 6), we believe, demands guidance mechanisms that both two- and four-year institutions seem to be unwilling or unable to support.12

Without a national longitudinal database, we can only guess at students’ trajectories through higher education, though we know from recent research that it is variable and, with regard to transfer students, often nonlinear (Hossler, Shapiro, Dundar, Ziskin, Chen, Zenquera, & Torres, 2012). Moreover, capacity is dependent on a series of countervailing, at times contradictory, variables, such as:

- The availability of public resources in the form of subsidies to two- and four-year institutions. Without these subsidies, two- and four-year institutions make up the loss by increasing tuition, an act that may depress the enrollment of all students but especially those attending community colleges.

- The availability of federal resources in the form of direct financial aid or greater access to subsidized federal loans. Given that community college students are more likely to come from lower socioeconomic backgrounds, the availability of financial support — Pell Grants, subsidized loans, work-study — is a vital element in their ability to complete a four-year degree.

- The degree to which four-year institutions want or need transfer students from community colleges. Four-year institutions, by and large, choose the number of transfer students they wish to enroll; it is rarely a mandated number. So, when leaders of these institutions say they are “at capacity,” it is important to remember they could potentially enroll more transfers by taking fewer freshmen.

What we lack is compelling information about the ability of two-year institutions to prepare additional students for transfer and the baccalaureate degree and the capacity and willingness of four-year institutions to admit more community college students to the upper division. National education trends offer some insight but on balance portray great uncertainty about the future viability of the transfer pathway.

Chapter 5: Incentives and Accountability

“Transfer should be a performance indicator for community colleges and for four-year schools. … Having transfer students be a part of the way the universities are judged is a wonderful way of improving retention.”

Member of the Commission on Transfer Policy and Practice