Transfer Access to Elite Colleges and Universities in the United States: Threading the Needle of the American Dream

The Study of Economic, Informational, and Cultural Barriers to Community College Student Transfer Access at Selective Institutions

Principal Investigators

Dr. Alicia C. Dowd

Assistant Professor, Graduate College of Education

University of Massachusetts Boston

Dr. Glenn Gabbard

Associate Director, New England Resource Center for

Higher Education (NERCHE)

University of Massachusetts Boston

Researchers

Dr. Estela Mara Bensimon

Professor and Director, Center for Urban Education

Rossier School of Education

University of Southern California

Dr. John Cheslock

Assistant Professor

University of Arizona

Dr. Jay R. Dee

Associate Professor, Graduate College of Education

University of Massachusetts Boston

Ms. Thara Fuller

Research Associate, New England Resource Center for

Higher Education (NERCHE)

University of Massachusetts Boston

Mr. David Fabienke

Research Associate

Tomás Rivera Policy Institute,

University of Southern California

Ms. Rhonda Gabovitch

Research Assistant, Graduate College of Education

University of Massachusetts Boston

Dr. Dwight Giles

Professor, Graduate College of Education

University of Massachusetts Boston

Ms. Nancy Ludwig

Research Assistant, Graduate College of Education

University of Massachusetts Boston

Dr. Elsa Macias

Senior Research Associate, Tomás Rivera Policy Institute

University of Southern California

Ms. Lindsey Malcom

Research Assistant, Center for Urban Education, Rossier

School of Education

University of Southern California

Ms. Amalia Márquez

Research Assistant

Center for Urban Education

Rossier School of Education

University of Southern California

Dr. Tatiana Melguizo

Assistant Professor, Rossier School of Education

University of Southern California

Dr. Jenny Pak

Research Associate

Center for Urban Education

Rossier School of Education

University of Southern California

Mr. Daniel Park

Research Assistant

Center for Urban Education

Rossier School of Education

University of Southern California

Dr. Tara L. Parker

Assistant Professor, Graduate College of Education

University of Massachusetts Boston

Ms. Sharon Singleton

Program Associate, New England Resource Center for

Higher Education (NERCHE)

University of Massachusetts Boston

Acknowledgments

Many individuals contributed to this study and provided invaluable assistance in preparing reports, including Brad Arndt, Leticia Bustillos, Andrea DaGraca, Linda Kent Davis, Martha Mullane, Melissa Read, Edlyn Vallejo Pena, John Saltmarsh, Ricardo Stanton-Salazar, and Ronald Weisberger. Special appreciation is extended to the many individuals at the institutions who agreed to be interviewed for this study and the students who shared their stories of the transfer experience.

Clifford Adelman, Anthony Broh, Anthony Carnevale, and Jeff Strohl shared their expertise generously in providing feedback on earlier drafts of the report. We are particularly appreciative of insightful conversations during the development of the research and ongoing support from David Cournoyer, Emily Froimson, Jay Sherwin, Heather Wathington, and Joshua Wyner.

Executive Summary

Nearly half of all undergraduate students are enrolled in community colleges—and that

percentage is on the rise.1 Among them are millions of full-time students, many from low-income

families and most of traditional college age (18-24).2 For these students, a community college

education can open doors to opportunity, including serving as a gateway to a four-year degree.

Yet many doors remain closed to even the most talented low-income community college students.

Nowhere are these limitations more apparent than in the limited opportunity community college

students are granted to transfer to the country’s most selective four-year institutions. Top community

college students struggle against the mistaken perception by some college administrators and others

that these students cannot succeed at elite institutions. They also face cultural and economic barriers

to completing their bachelor’s degrees.

Although full-time community college enrollment is growing faster than enrollment at four-year

schools,3 the opportunity to transfer to elite institutions is shrinking. In 1984, 10.5% of entering

students at elite private four-year schools were transfer students; by 2002 that number had dropped

to only 5.7%. The data suggest that fewer than one of every 1,000 students at the nation’s most

selective private institutions is a community college transfer (Dowd & Cheslock, 2006).

Meanwhile, the talent pool at community colleges is large and growing. Students who manage to

transfer complete their bachelor’s degree programs at high rates. Seventy-five percent of community

college transfers attending selective institutions completed their bachelor’s degrees within 8.5 years of

high school graduation. The study shows that the lowest-socioeconomic status (SES) community

college students who transfer to elite institutions are more likely to graduate than low-SES students

with similar characteristics who started at four-year schools (Melguizo & Dowd, 2006).

Some highly selective four-year schools have recognized this talent pool as well as the barriers

community college transfer students face and have made a significant effort to enroll more of them.

Likewise, some community colleges have encouraged students to pursue elite four-year schools

(Gabbard, Singleton, Bensimon, Dee, Fabienke, Fuller, et al., 2006). But, much more can be done.

Together, highly selective institutions and community colleges have the potential to dramatically

increase the number of low-SES transfer students by encouraging talented community college students

to apply, raising awareness of financial aid, and working to diminish cultural barriers. A

committed effort would not only create opportunity and reward student talent, it would also improve

diversity at elite schools.

Unlimited Possibilities and Limited Probabilities

The social historian David Labaree (1997) has described the educational system of the United States as one of “unlimited possibilities and limited probabilities.” Due to a distinctly American mix of political ideals and economic imperatives, the door never closes on the hopes of individuals wishing to better themselves through education. In the highly stratified arena of post-secondary education, community colleges are the home of second chances and fresh starts, attracting students of a wide range of academic abilities and financial means.

The Study of Economic, Informational, and Cultural Barriers to Transfer Access at Selective Institutions examined the opportunities and barriers surrounding transfer to the most elite colleges and universities in the United States for low-income community college students. The study was undertaken in response to a call for research from three foundations concerned about low-income students’ access to college: the Jack Kent Cooke Foundation (JKCF), Lumina Foundation for Education, and Nellie Mae Education Foundation.

In addition, the study informed a broader effort, called the Community College Transfer Initiative (CCTI), by the Jack Kent Cooke Foundation to increase transfer access for low- to moderate-income community college students to elite4 colleges and universities in the United States. The impetus for the study and the CCTI is a pressing concern for educational equity raised by the limited number of low-income students enrolling in and graduating from elite institutions (Bowen, Kurzweil, & Tobin, 2005; Carnevale & Rose, 2004), particularly given the entree such institutions provide to positions of leadership in our society. As the CCTI has sought to emphasize, considerable damage is done to the democratic foundations of our educational system when the vast numbers of students who start their postsecondary education at a community college are essentially excluded from the opportunities and benefits of study at an elite college or university.

In keeping with the goals of the three foundations and the CCTI, The Study of Economic, Informational, and Cultural Barriers investigated the degree to which low-income community college students have access to the most highly selective institutions in the United States, as well as the attitudes and practices that facilitate and obstruct that access. The findings of our study of transfer access reinforce Labaree’s (1997) thesis that the educational system is characterized by “unlimited possibilities and limited probabilities.” Labaree roots this contradiction firmly in a class-based society that never absolutely precludes the possibility of social mobility, but at the same time structures educational opportunities that put poor and working class students at a disadvantage. “The probability of achieving significant social mobility through education is small, and this probability grows considerably smaller at every step down the class scale,” he has written (p. 41).

For the least affluent in our society, the chances of transferring from a community college to an elite institution are practically negligible. Yet, each year a small number of students bridge the divide of culture, curriculum, and finances in a move that epitomizes the cherished American Dream of social mobility. This study documents that limited opportunity, and explores practices that might be used to increase the rate of low-income transfers.

Accidental Transfer: Advising Is Key But Haphazard

The study brings to light the stories of socioeconomically disadvantaged community college students who have transferred to elite institutions. A high school honors student chooses her local community college over a four-year university in order to save her family money. A young man, serious about his studies for the first time, makes his way through college by working full time and placing tuition charges on his credit card. Homeless when her parents lose their jobs just after she completes high school, a young woman grows ever more determined to earn her bachelor’s degree. A middle-aged truck driver leaves behind the world of 18-wheelers when her brain is “set on fire” by her critical thinking professor at the community college (Pak, Bensimon, Malcom, Marquez, & Park, 2006).

A key finding of the study— that critical relationships between transfer counselors and students at community colleges have a haphazard, “accidental” quality— suggests the need for greater institutionalization of the perspectives and experiences of transfer students in recruitment, admissions, and financial aid offices. Without structured interventions and active faculty involvement, students must rely on being in the right place at the right time to connect with trusted advisors who can help them.

These stories, though inspirational, are rare. The number of economically disadvantaged community college transfer students enrolling in the uppermost strata of selective institutions, the “elites” of American higher education, may be as few as 1,000 students annually (Dowd & Cheslock, 2006). Those students who make the journey from community colleges to elite institutions, particularly those who are the first in their family to attend college, must be highly motivated. Lacking models of educational success in their families, and often having been told in ways subtle and direct that they are not “college material,” the transition is not simply one of time and physical space, but also of identity (Pak et al., 2006). A key finding of the study—that the critical relationships between transfer counselors and students at community colleges have a haphazard, “accidental” quality— suggests the need for greater institutionalization of the perspectives and experiences of transfer students in recruitment, admissions, and financial aid offices. While the efficacy of these activities are yet unproven, examples revealed through the study include such practices as helping students navigate complicated academic requirements and application procedures, validating students’ educational aspirations, and dispelling students’ fears that they do not belong. The examples demonstrated that without structured interventions and active faculty involvement, the successful transfer students often needed to be in the right place at the right time to connect with trusted advisors who could help them. It was up to them to recognize the value of unfamiliar opportunities and take advantage of them when they had the chance.

The focus and determination required to transfer from a community college to an elite institution suggests that economically disadvantaged students who do so are “threading the needle of the American Dream”— navigating a sliver of opportunity for social mobility.

Increasing Talent at Community Colleges, Decreasing Transfer Rates

The reality that small numbers of economically disadvantaged students transfer to elite institutions reveals the limitations of access and opportunity. The community college as a “grand and ongoing democratic enterprise” (Sullivan, 2005, p. 142) is circumscribed by limits that bar entree into elite institutions. As Patrick Sullivan writes in Teaching English in the Two-Year College, the “archetypal American cultural narrative” that hard work and self-improvement leads from “rags” to “riches” is undercut in the eyes of poor and working-class community college students, who “have been taught by harsh economic realities that classic American ‘happy endings’ do not apply to them” (p. 146). As a result, students “clearly understand that class is a powerful reality in America, and they feel its inequities sharply” (p. 145).

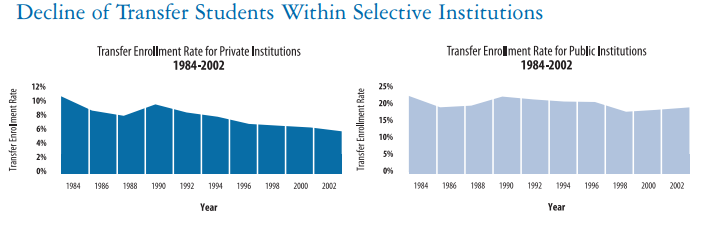

The study finds that, over time, transfer access from both two- and four-year colleges to elite institutions has become even more constricted. From 1984 through 2002, the share of transfer students among the entering student class declined from 10.5% to 5.7% at the highly selective private institutions, and from 22.2% to 18.8% at the public selective institutions. The trend since 1990 has been strictly downward in the private sector, while the public sector experienced a slight rebound from a low of 15.8% in 1999 (Dowd & Cheslock, 2006).

Nearly 26,000 students from

the class of 1992 who started

at community college had

earned high school grades

that put them in the top fifth

of their class.

Among the few community college transfer students who managed to gain entry to institutions with selective admissions, only 20% were from low-income households, defined as the lowest two quintiles of a socioeconomic status index available in the national data analyzed.

At the same time, the pool of academically talented students at the community college became larger. In comparison to earlier cohorts, graduates in the high school class of 1992 who started at a community college had higher levels of mathematics preparation—13 percent completed calculus or pre-calculus in high school. Nearly 26,000 students from the high school class of 1992 who started at a community college had earned high school grades that put them in the top fifth of their class (Melguizo & Dowd, 2006).

Making It: Transfers at Elite Institutions Attain Their Bachelor’s Degrees

In the study, those community college transfers who did manage to gain access to four-year institutions at highly selective and selective institutions graduated in high numbers. Seventy-five percent completed their degrees within 8.5 years of graduating high school, a figure that our research suggests increases to 80% or 90% at the most elite institutions. The chances for bachelor’s degree attainment at non-selective institutions, where transfer students are concentrated, are much lower, with only about half the students receiving a bachelor’s within that time frame (Melguizo & Dowd, 2006).

Even when taking into account student characteristics such as academic preparation and socioeconomic status, the research showed that selectivity of the four-year institution had a powerful impact on the eventual probability of graduation. An increase of 100 points in the average SAT scores at the four-year institution is associated with a 4% increase in a student’s probability of degree completion. The chances of degree completion increase 26% for students at the highest level of institutional selectivity compared to those at the lowest level.

75% of community college transfers at selective four-year institutions complete their degrees. Research suggests that number increases to 80% or 90% for students who transfer to the most highly selective institutions.

Community colleges provide a cost-effective pathway to the bachelor’s degree for academically prepared, highly motivated students—if they manage to transfer to a selective institution.

In addition, the findings of the study showed that low-SES transfer students with aspirations to earn a bachelor’s degree5 were not disadvantaged in their chances of achieving that goal by starting at a community college. Among both transfer and native four-year college students (students who attend a four-year institution from the start of their higher education), as SES increases, the probability of degree completion also increases. However, the rise is distinctly steeper for natives, indicating that SES has a stronger effect on the bachelor’s degree completion of those enrolling directly in the four-year sector. At the lowest levels of SES, transfer students even have a slight edge in bachelor’s degree completion over their counterparts who started in the four-year sector (Melguizo & Dowd, 2006). These findings indicate that community colleges provide a cost-effective pathway to the bachelor’s degree for academically prepared, highly motivated students—if they manage to transfer to a selective institution. This contingency is not trivial because, as the findings of the study also show, only a small number of students manage to do so.

Widening the Pipeline for Transfer: Economics Drives Access

Despite the growing presence of academically prepared students at community colleges, and the high rates of degree completion among those transfer students who do enroll at institutions with selective admissions, elite colleges and universities fall far short of providing equitable access for this pool of talent. In fall 2002, the estimated number of two-year transfers entering elite institutions in the United States was just over 11,000 students. More than half of these were in the public sector, and only three percent were in liberal arts colleges. Of these 11,000, as few as 1,000 were students from socioeconomically disadvantaged households (Dowd & Cheslock, 2006).6

Elite colleges and universities fall far short of providing equitable access for this pool of talent.

To promote greater transfer access to elite institutions, it is important to have an understanding of the institutional incentives and barriers to enrolling transfer students. To a great extent, an elite institution’s enrollment capacity beyond the freshman year determines its receptivity to transfer students. The findings of the study, based on a statistical analysis of data from the College Board’s Annual Survey of Colleges,7 indicate that four-year institutions with relatively high rates of student attrition from the first to second years of college are those most likely to admit transfer students in greater numbers. Comparing cases with similar characteristics of institutional type, sector, enrollment size, admissions rate, geographic location, tuition and other factors, a 10% increase in student attrition is associated with a 5% increase in the transfer enrollment rate (Dowd & Cheslock, 2006).

These results imply that colleges with relatively high departure rates from their freshmen classes turn to transfer students to replenish enrollment and fill classrooms, particularly in upper-level seminars that might otherwise go undersubscribed. Facing economic pressures due to high attrition, colleges can fine tune their enrollment by admitting upper-level transfers. This strategy may be preferable to enrolling a larger freshman class in subsequent years, because a higher admissions rate would lower the institution’s ranking in selectivity and prestige indicators. Further, enrolling a larger freshman class may not be an option due to space limitations in introductory lecture halls, required freshman composition seminars, and residence halls.

As few as 1,000 community college transfers from socioeconomically disadvantaged households enroll in selective and highly selective colleges each year.

The results also showed that, even controlling for the larger size of public institutions, public institutions have a 7% higher transfer enrollment rate than private universities. These findings undoubtedly reflect the obligation of public institutions to provide equal access to college and demonstrate the effects of state policy on enrollment rates.

Findings suggest that transfer enrollment decisions are driven by institutional economics, rather than other institutional values, such as commitment to educational equity and diversity.

The strength of attrition and other enrollment characteristics as indicators of an institution’s transfer amenability reveals the primary role of institutional economics in determining transfer access. In combination with the overall low numbers of community college transfer students at elite institutions, these findings suggest that transfer enrollment rates are driven by institutional economics more than other institutional values, such as commitment to educational equity and diversity. Thus, it seems that elite institutions have yet to fully embrace the value of admitting community college transfer students as a way of increasing the economic and racial diversity of their own student bodies.

Transfer Agents and Transfer Champions as Cultural Brokers and Advocates

Community college students need community college faculty and administrators to encourage them to apply to elite schools, and help them with the application process, including by providing information about financial aid. They also need elite four-years to affirmatively encourage community college students to apply, help them through the financial aid process, and overcome social and cultural barriers.

Individual administrators and faculty can act on their own or collectively to increase transfer access.

Analysis of interviews with administrators, faculty members, and students who successfully transferred from a community college to an elite institution demonstrated that individual administrators and faculty can increase transfer access either by acting on their own or collectively. To learn about exemplary8 transfer policies and practices at community colleges and elite four-year colleges and universities, site visits were conducted at eight “best practice” pairs of institutions. These institutional exemplars were identified based on the numbers of community college students transferring to the elite institution, and on signs of a relatively high level of programming and advising to facilitate transfer access, as indicated by a review of institutional admissions and program documents (Gabbard et al., 2006). In addition, ten life history interviews were conducted with students who successfully transferred from a community college to an elite institution (Pak et al., 2006).

The findings of the study demonstrated that administrators and faculty members play two critical roles in helping students traverse the boundaries between open access and exclusive institutions: transfer “agents” (Pak et al., 2006) and transfer “champions” (Gabbard et al., 2006).

Transfer students and the trusted agents who help them often meet more by accident than design.

We build on the sociological notion of “institutional agents” (Stanton-Salazar, 1997) and use the term “transfer agents” to refer to authority figures who, in helping students navigate complicated academic requirements and application procedures, also validate students’ educational aspirations and dispel fears of not belonging (Pak et al., 2006). Transfer “champions,” in contrast, are administrators and faculty members with a commitment to educational equity who advocate for administrative practices that promote transfer access. Transfer champions represent the views of transfer students, socioeconomically disadvantaged students in particular, to shape institutional policies and practices in ways that are amenable to the transfer student experience (Gabbard et al., 2006). Transfer “agents” and “champions” are often former transfer students themselves and are motivated by an appreciation of the complexity of student experiences, particularly the barriers many students have overcome to enter postsecondary education. Individuals who play a strong role as advocates for institutional change tend to have empathy for the community college student based on personal experiences.

The characterization of transfer students as “late bloomers”—those who do not discover their full academic potential or capacity until after they leave primary education (Pak et al., 2006)—emphasizes the important role of transfer agents in assisting student development. Students can be late bloomers due to any number of circumstances, including that they were not given serious consideration in school as a result of a working-class background, or that their parents lacked information about the educational financial aid system in the United States. Other students are late bloomers because, as minority, low-income, first-generation students, the possibility of attending college was never presented to them while they were in high school—they were not considered college material. Such students cannot easily imagine themselves at elite institutions.

The study shows that transfer students and the trusted agents who help them often meet more by accident than by design. A faculty member, a dean, or an administrator happened to notice the student and reached out to him or her. One student who was interviewed explained that, by happenstance, she saw an announcement about a summer program being offered at the elite college to which she eventually transferred. When she went to the dean’s office to get more information, the dean was “excited and very welcoming,” and “instead of saying well, that person is up there and, you know, instead of [just] pointing the direction, she actually escorted me there.”

Individuals who are “transfer agents” demonstrate “authentic caring” (Valenzuela, 1999) through concrete actions. They do more than impart information or act as role models. Authentic caring is expressed affectively and instrumentally.

The difference between someone who is a “transfer agent” and someone who is not can be more fully appreciated by contrasting the same student’s description of her transfer counselor as “very gruff” and “just wanting to get the job done.” She said, “It was like, okay, this is what you need to complete. It wasn’t the one-on-one connection that I felt with my academic dean” (Pak et al., 2006).

Just as some individuals act as “transfer agents” through their personal relationships and authentic caring for students, others act in relation to administrative and faculty colleagues as “transfer champions,” representing equity perspectives and the transfer student point-of-view in administrative and curricular decision making. For example, at Pendleton University, the diversion of resources from low- to middle- income students in a transfer preparation program was brought to light by an executive university administrator who insisted on regular evaluation of the demographic characteristics of the students served by the community college honors programs. Because this evaluation included data on students’ income and racial/ethnic identity, the mission shift was discovered. This “champion” also led a fundraising drive to create endowed scholarships for transfer students.

Other examples of the activities of “champions” revealed through the case study included creating structures such as student speakers’ panels to enable faculty and administrators to hear about transfer students’ experiences in their own voices; ensuring transfer student representation on curriculum committees; participating in transfer pathway consortia involving community colleges, universities and secondary schools; and taking part in meetings and public events at partner colleges. Similarly, faculty members who acted as transfer “champions” were active in curriculum planning processes involving both four-year and community college faculty, which led to dialogue about pedagogy, assessment of student merit, and advising practices in the two sectors (Gabbard et al., 2006).

Reducing Informational and Cultural Barriers to Transfer

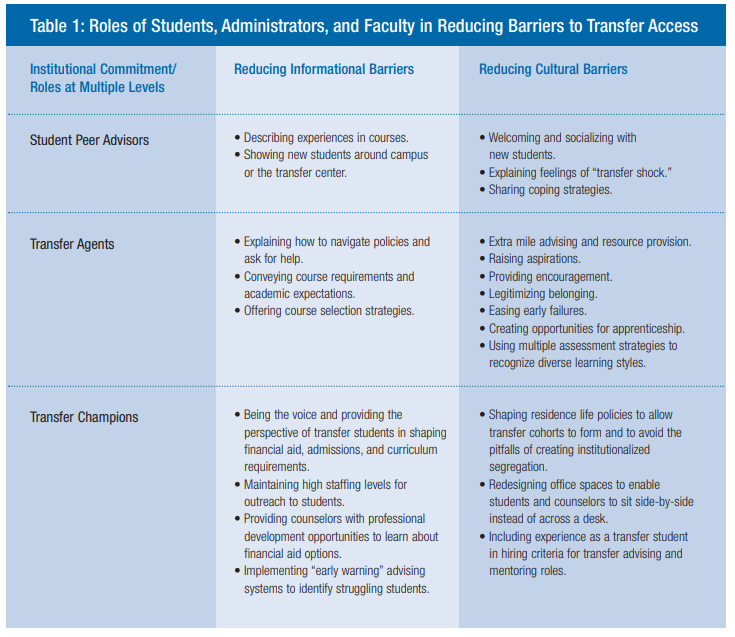

At community colleges and four-year colleges, individuals can reduce informational and cultural barriers for transfer students by serving in one of three critical roles illuminated by our study: peer advisor, “transfer agent,” and “transfer champion.” Table 1 shows ways in which individuals acting in these roles can help increase transfer access by building relationships, sharing information, offering peer and professional support, and advocating for community college transfers at the institutional or policy level.

Peer advisors, transfer agents and transfer champions all serve interrelated roles in reducing both informational and cultural barriers. Peer advisors not only provide new and prospective transfers with valuable translations of bureaucratic and academic requirements, but can also play a role in providing encouragement and support to new transfers. Prospective transfers can read about application procedures and course prerequisites in a brochure or online, but personal contact from a peer advisor makes a difference in acculturating students to college life. More experienced students can also counsel new transfers with “transfer shock,” which many transfers experience when they discover they are no longer consistently the top student in the class. Personal relationships with advanced transfer students can help new and prospective transfers build their aspirations and academic confidence.

Other research suggests that peer advisors themselves are empowered by roles that place them in positions of authority and allow them to draw on their specialized knowledge to help other students (Tierney & Venegas, forthcoming). This empowerment creates additional capacity for peer advisors to inform the work of transfer champions by joining administrative committees or making presentations to college faculty members.

Like peer advisors, transfer agents provide valuable information for navigating policies, procedures, and course requirements. Their most critical role, however, is to break down cultural barriers and help students learn what it takes to succeed at college.

One student interviewed said that orientation for community college transfers had been web-based, not in person. This is a problematic advising strategy because many students learn more effectively through human interaction. Web sites can pose additional barriers as well because they are frequently out-of-date or unwieldy in their design. An exploratory study of web-based transfer information (Adelman 2006, p.1) concluded: “Part of what makes for future success in the community college is student understanding of where one is going, why and what it takes to get there. Misinformation, half-understood information or gaps in information can have deleterious consequences. More damaging, still, is a Web portal that makes no attempt to segment the populations of its users, so that prospective students have no clue of where to enter the links of information that lie on lower page levels.” As a result, online (as well as print) advising and counseling resources should always be combined with personal advising.

An administrator at a selective institution (Gabbard et al., 2006) explained that orientation for first-time freshmen students is the norm, while orientation for transfer students is often seen as unnecessary:

There are a few [faculty advisors who] would have transfer students take two very rigorous courses at the same time, which we would not have any of our first-year students take at the same time. I think of organic chemistry and one of our genetics courses, which are among the most challenging in the college. Some of us advisors would not have any of our students take both of those courses in the same semester, but some advisors would have a transfer student come in and take something like that instead of easing their way into it during their first semester.

Here, the administrator is recognizing that even community college transfer students who have adequate academic preparation still need a period of socialization to transfer successfully. A faculty member acting as a transfer agent might advise a transfer student to take only one of these two difficult courses and pair that course with a seminar, independent study, or research assistantship in the sciences—all of which are much more likely to afford an opportunity for an apprenticeship in which the student can develop a close working relationship with the professor and become socialized to academic work.

The most comprehensive strategies for increasing transfer access effectively are those that bridge the world of the community college and the elite four-year campus. These strategies provide information, acculturation, and “transfer shock inoculation” (Pak et al., 2006) through a range of programs: residential and intensive short-term academic programs that bring community college students to the four-year campus prior to transfer; cohort programs that create niche communities and networks of support for transfer students; and honors programs at the community colleges that instill academic self-confidence and ensure that students’ course credits will “count” at an elite college.

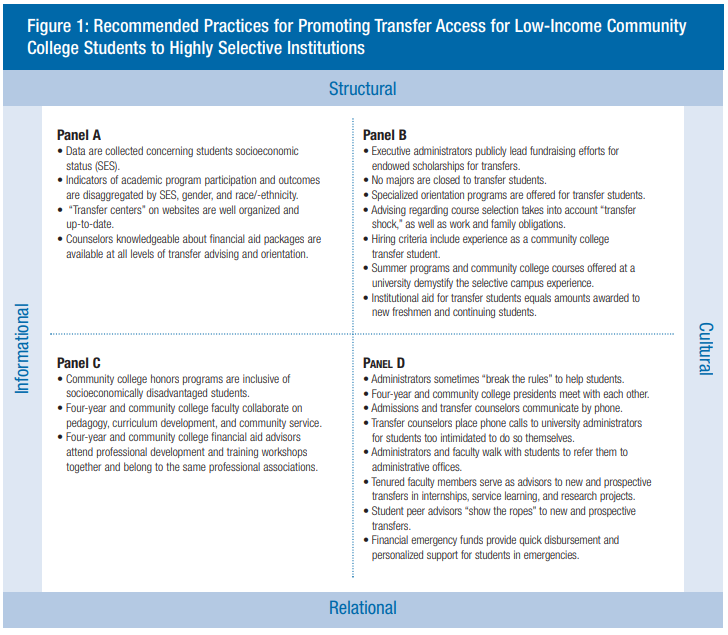

The findings of our study offer guidance to institutions that wish to develop a transfer-amenable culture. (See Figure 1: Recommended Practices for Promoting Transfer Access for Low-Income Community College Students to Highly Selective Institutions.) This guidance includes informational and cultural recommendations for structural administrative changes as well as shifts in relationships among administrators, faculty, and students of four-year and community colleges.

In order to develop a transfer-amenable culture with access for socioeconomically disadvantaged students, institutions must adopt the practices and policies shown in the intersection of structural-relational and informational-cultural dimensions of Figure 1. In this figure, the structural dimension refers to how policies and practices are carried out, by whom, and with what level of resources. The relational dimension focuses on the ways these practices and policies bring administrators, faculty, and students at two-year and four-year colleges together into professional communities of practice, learning communities, and social networks.

The recommendations (Panel A) show the necessary steps for examining and creating appropriate conditions of transfer access, such as collecting data on student socioeconomic status, providing financial aid information to students, and keeping web sites current. They also highlight ways to shape the culture of an institution (Panel B). For example, when administrative leaders make public commitments to transfer students or when they adopt policies to ensure that transfers have access to every major offered by a college, they demonstrate that transfers are equal members at a highly selective institution—not second-class citizens who are simply allowed to fill in available spaces. To bridge the gap between community colleges and elite institutions, we recommend practices that recognize cultural differences, such as specialized orientation and advising programs, and, for prospective advisors, a hiring criterion of personal experience with transfer (Gabbard et al., 2006).

Relationships among four-year and two-year administrators, faculty, and students are conduits for critical information and transfer access (Panel C) and some of their actions have important symbolism (Panel D). Honors programs, faculty consortia, professional associations and task forces create important social networks for sharing information and creating knowledge about how transfer works, or doesn’t. This knowledge is critical—both for students who want to transfer and for faculty and administrators who want to change transfer practices on their campuses. These symbolic behaviors are surprisingly simple, yet the case study findings clearly showed the importance of personal gestures in easing feelings of intimidation among students, as well as feelings of condescension that are commonly perceived by community college faculty and administrators who interact with colleagues from more prestigious institutions.

Our recommendations emphasize financial aid in every aspect of practice because it is such a key component of transfer access to elite institutions. The financing environment students experience in community colleges differs significantly from the one students experience in the four-year sector, particularly at private institutions. For example, in 2003-04, 73% of bachelor’s degree recipients of private nonprofit institutions graduated with federal and nonfederal loan debt, with median debt levels equal to $19,400. (At public fouryear institutions, 62% of students borrowed, with a median debt of $15,500.) In contrast, only 35% of community college graduates had taken loans and their median debt level was much lower, at $6,100 (Trends in Student Aid, 2005).

Institutional aid is another major source of financial aid at private colleges, where it often significantly offsets the institution’s sticker price for low-income students. The College Board (Trends in Student Aid, 2005) reports that in academic year 2003-049 at the highest priced private colleges (tuition and fees $25,350 and greater), average institutional grants to students from the lowest family income quartile equaled $11,100. Not surprisingly, with their significantly lower tuition and fee levels, average institutional aid at community colleges was only $300.

The very different financial aid environments create a financing gulf that transfer students need particular help in navigating. Due to the complexity of the financial aid system, socioeconomically disadvantaged students and their parents may not have the knowledge and resources to decipher their aid eligibility and the ultimate net price of college (Gabbard et al., 2006; Kane, 1999; King, 2004; Student Aid Gauntlet, 2005). As a result, transfer students need to have knowledgeable financial aid counselors available at all transfer advising and orientation activities. Moreover, community college and four-year college financial aid advisors should participate in professional development activities together in order to gain an understanding of their different financing environments.

One elite university reported that its financial

aid policies changed recently after administrators

gained a better sense of the financing

pressures on transfers.

One elite university that participated in site visits for this study reported that its financial aid policies recently changed after administrators gained a better sense of the financing pressures on transfers (Gabbard et al., 2006). The previous policy had required transfers to assume a debt level during two years at the college equal to the amount accumulated by students enrolled there for a full four years. This policy essentially placed a large debt penalty on students who had experienced a financial savings at the community college and significantly widened the financial aid gulf between the two sectors. The new policy replacing loans with institutional aid represented a significant cultural shift at this institution. Ensuring equal provision of institutional grant aid to transfers and native four-year college students is one of the most important steps a four-year institution can take to ensure transfer access. Awarding some of that aid in the form of highly publicized scholarships dedicated to community college transfers through specially endowed funds greatly enhances the cultural and informational aspects of such a financial commitment.

Creating a Transfer-Amenable Culture

Transfer champions are key to increasing transfer access. By institutionalizing the role of the transfer champion, colleges can ensure representation of transfer perspectives on recruitment, admissions, financial aid, curriculum, and student affairs committees. Likewise, transfer agents are essential to breaking down transfer barriers. Colleges must provide these agents with the resources and administrative flexibility to reach out to students “where they live” and engender trust, even when it means acting outside the norms of administrative routines and providing “extra mile advising.”

This kind of personal support taken by some transfer agents interviewed for this study included lending money or a car to students; visiting them at home when they are ill or in crisis; watching their child for a few hours when lack of a babysitter might otherwise ruin a student’s chances of passing an exam. While these actions suggest possible institutionalization of administrative support—such as financial emergency funds and drop-in day care services—transfer agents cannot be institutionalized. Rather, the key is to support equal opportunity programs, residence-based cohort programs, and transfer advising resource centers that create community-based environments of trust and caring. Resources should be provided to these programs with a small amount of “slack” in the budget to be deployed judiciously by transfer agents trusted by the college and students alike.

The practices highlighted above provide benchmarks for community colleges and elite institutions to examine their transfer practices and transfer culture. As transfer agents and champions, individual faculty members and administrators can significantly improve transfer access, especially given the very small numbers of socioeconomically disadvantaged students currently making their way across the boundaries of exclusivity.

The key implications of the study for community colleges and highly selective institutions wishing to increase transfer access are:

- Institutionalize the perspectives of transfer students in recruitment, admissions, and financial aid offices, and on curriculum committees by including former transfers in administrative and faculty roles or by asking current and prospective transfers to inform the work of those offices or committees based on their experiences.

- Support programs and people that create trusting community environments and provide “extra mile advising” to transfer students.

- Provide institutional aid in equal amounts in the financial aid awards of transfer and native four-year students through endowed scholarships dedicated to transfer students. Announce the award of these scholarships and the accomplishments of award winners through extensive media publicity to enhance the cultural and informational aspects of this financial commitment.

- Conduct data collections, program evaluations, and assessments of participation and academic performance in transfer programs to ensure extra resources intended to expand access are directed to socioeconomically disadvantaged students.

The last point is critical. Administrators and faculty who wish to observe the transfer conditions on their own campuses, as well as on the campuses of partnering institutions, must continue to evaluate program effectiveness and assess institutional transfer culture in order to successfully promote transfer access.

References

Adelman, C. (2006). Lost before translation: What high school students experience on community college web sites— an exploratory study.” Paper presented at the Council for the Study of Community Colleges, Long Beach, CA.

Bowen, W. G., Kurzweil, M. A., & Tobin, E. M. (2005). Equity and excellence in American higher education. Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press.

Carnevale, A. P., & Rose, S. J. (2004). Socioeconomic status, race/ethnicity, and selective college admissions. In R. D. Kahlenberg (Ed.), America’s untapped resource: Low-income students in higher education: Century Foundation Press.

Dowd, A. C., & Cheslock, J. J. (2006). An estimate of the two-year transfer population at elite institutions and of the effects of institutional characteristics on transfer access. Boston, MA and Tucson, AZ: University of Massachusetts Boston and University of Arizona.

Gabbard, G., Singleton, S., Bensimon, E. M., Dee, J., Fabienke, D., Fuller, T., et al. (2006). Practices supporting transfer of low-income community college transfer students to selective institutions: Case study findings. Boston, MA: University of Massachusetts Boston.

Kane, T. J. (1999). The price of admission: Rethinking how Americans pay for college. Washington: Brookings Institution Press.

King, J. E. (2004). Missed opportunities: Students who do not apply for financial aid. Washington, D.C.: American Council on Education.

Labaree, D. F. (1997). How to succeed in school without really learning: The credentials race in American education. New Haven: Yale University Press.

Melguizo, T., & Dowd, A. C. (2006). National estimates of transfer access and bachelor’s degree attainment at four-year colleges and universities. Los Angeles, CA and Boston, MA: University of Southern California and University of Massachusetts Boston.

Pak, J., Bensimon, E. M., Malcom, L., Marquez, A., & Park, D. (2006). The life histories of ten individuals who crossed the border between community colleges and selective four-year colleges. Los Angeles, CA: University of Southern California.

Stanton-Salazar, R. D. (1997). A social capital framework for understanding the socialization of racial minority children and youths. Harvard Educational Review, 67(1), 1-40.

The student aid gauntlet: Making access to college simple and certain. (Final Report of the Special Study of Simplification of Need Analysis and Application for Title IV Aid)(2005). Washington, D.C.: Advisory Committee on Student Financial Assistance.

Sullivan, P. (2005). Cultural narratives about success and the material conditions of class at the community college. Teaching English in the Two-Year College, 32(2), 142-160.

Tierney, W. G., & Venegas, K. M. (forthcoming). Fictive kin and social capital: The role of peer groups in applying and paying for college. Amercian Behavioral Scientist.

Trends in student aid. (Trends in Higher Education Series)(2005). Washington, D.C.: College Board.

Valenzuela, A. (1999). Subtractive schooling. New York: SUNY Press.

End Notes

1 Adelman, C. (2005). Moving into town–and moving on: The community college in the lives of traditional-age students. Washington, D.C.: U.S. Department of Education.

2 Adelman, C. (2005).

3 U.S. Department of Education, National Center for Education Statistics, Higher Education General Information Survey (HEGIS), “Fall Enrollment in Colleges and Universities” surveys, 1969 through 1985; and 1996 through 2002 Integrated Postsecondary Education Data System, “Fall Enrollment Survey” (IPEDS-EF:96-99), and Spring 2001 through Spring 2003.

4 These are institutions categorized as most or highly competitive in Barron’s Profile of American Colleges. The terms “elite” and “highly selective” are used interchangeably in this report to refer to the group of institutions that are the focus of the Community College Transfer Initiative.

5 See Melguizo & Dowd (2006) for detailed definitions of the methods and samples of the analysis.

6 This estimate is presented cautiously due to the lack of data measuring student income or socioeconomic status at elite institutions. The national estimate is not adjusted for potentially larger numbers of low-income transfers in California and other states with large public higher education systems that may be effective in providing transfer access to flagship universities for their least affluent residents.

7 Source of Data: the Annual Survey of Colleges of the College Board and Data Base, 2004-05. Copyright 2004 College Entrance Examination Board. All rights reserved.

8 Practices and policies are termed “exemplary” because they were observed in use at institutions selected through exemplary case sampling and emerged as important through triangulation of data from document analysis and interviews with administrators, faculty, and transfer students. The identification of these practices is further supported by sociological and educational theories of student development. Thus, the “exemplary practices” provide benchmarks for institutions to assess their transfer amenability, but the case study research did not examine or evaluate the effectiveness of these practices.

9 The College Board analysis is based on data from the National Postsecondary Student Aid Study (NPSAS: 2003-04).