Equal Talents, Unequal Opportunities, Second Edition: A Report Card on State Support for Academically Talented Low-Income Students

Introduction

A growing body of research offers evidence that high-ability students from lower-income families are far less likely than wealthier students to be identified for advanced level course work and opportunities.* They are also less likely to achieve at high levels, despite their aptitude.¹ Lacking access to the enriched academic opportunities, differentiated learning, and counseling afforded to wealthier students, high-ability, low-income children are becoming what one team of researchers has termed a persistent talent underclass — underserved and therefore prevented from fully developing their talents.²

Since 2000, the Jack Kent Cooke Foundation has been committed to supporting the education of exceptionally promising students with financial need. The Cooke Foundation issues this periodic state-by-state analysis to measure state policy support for advanced learning and to highlight disparities in educational participation and outcomes of advanced learners from low-income families. This report measures the extent to which states are addressing the needs of high-ability, low-income students, and identifies best practices that states may adopt.

In the three years since we published the first edition of Equal Talents, Unequal Opportunities, we are pleased that policymakers and educators have noted greater interest in addressing the country’s high-ability, low-income students.³ Income-based discrepancies in educational attainment and opportunity have increasingly been a topic discussed in the mainstream media.⁴

“States, along with local educators and parents, are the most critical actors working to ensure that every child has access to a quality education.”

In light of this increased attention, this report assesses state progress in increasing support for high-ability, low-income students. The Every Student Succeeds Act (ESSA), passed in December 2015, places considerable responsibility and autonomy for ensuring student success in the hands of individual states. Indeed in her letter to Chief State School Officers, Education Secretary Betsy DeVos writes that “States, along with local educators and parents, are the most critical actors working to ensure that every child has access to a quality education.”

Yet state plans have come under criticism for not doing enough to ensure equity of opportunity regardless of family income, or having sufficient focus on high-ability students.⁵

This report examines which states have implemented policy changes that can help close excellence gaps. More importantly, we identify those states in which we see improved participation and achievement for high-ability, low-income students. Our goal for this research is to illustrate the excellence gap using indicators that are readily available, easily understood, and comprehensive. We seek to provide clear guidance to states on how they may better support advanced learning for all students, by implementing policies to ensure that all high-ability students — including those from low-income backgrounds — have the support they require in order to develop their talents.

*All students have talent and ability. We use the terms “high-ability” and “advanced learners” to refer to students with the intellectual capacity to reach high levels of academic performance in school. We use the term “low-income” to identify students’ family financial resources (as opposed to “low-SES” or “economically vulnerable”) because most of the data indicators included use some proxy of family income (free or reduced price lunch status, for example) to identify students. This by no means is intended to de-emphasize the importance of social capital in nurturing students’ academic potential.

What We Did

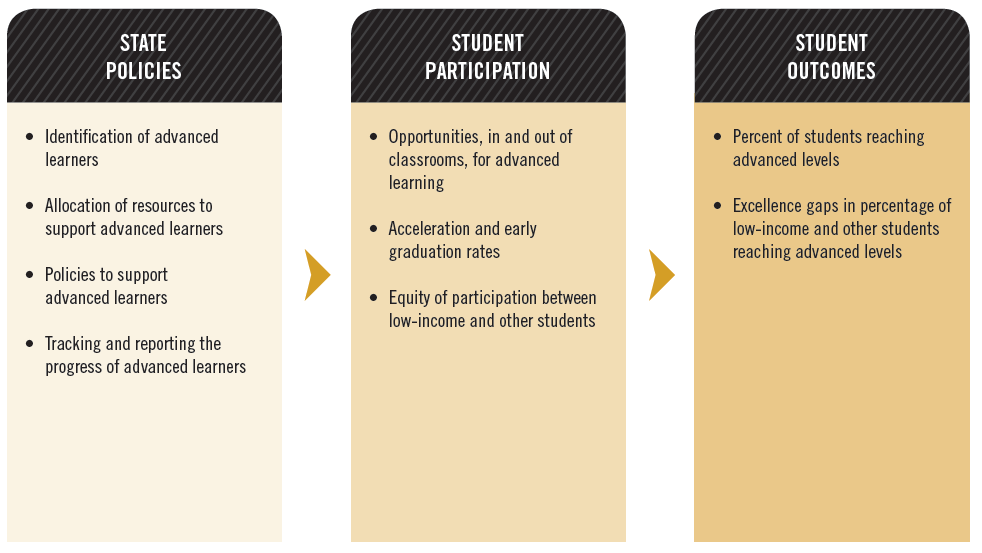

This project began in 2014. In conjunction with an advisory board of national experts familiar with the landscape of state policy as it relates to advanced learning, the project team compiled a master list of indicators that could be used to evaluate the extent to which state-level policies are in place, the degree to which students are participating in targeted interventions, and students’ success in attaining advanced levels of achievement.6 We organized these indicators into a project logic model (Figure 1), and selected 28 of these indicators to include in this year’s report.

We are pleased we were able to include more indicators this year than previously. Fifteen indicators from the 2015 report and 13 new indicators are included in this year’s report (Figure 2).7 This report also improves upon the 2015 report with the inclusion of data on student participation, to measure opportunity gaps.

In a major departure from the earlier report, we have grouped indicators separately into measures of Excellence (achieving advanced educational learning outcomes for all students) and Closing Excellence Gaps (decreasing discrepancies between a state’s low-income students and other students in reaching advanced levels of achievement). Policies were mapped to these two areas based on recent research on policy effectiveness; if there is demonstrated evidence that a policy leads to smaller excellence gaps, then that policy was listed as an excellence gap measure.

A well-taken criticism of the earlier report was the degree to which a state with favorable excellence policies and data but a poor track record with excellence gaps could score well overall. Separating “Excellence” from “Closing Excellence Gaps” better allows us to highlight states that are doing well in both areas. It also allows for a state to score well in its support and outcomes for advanced learners in general, but score poorly for support and outcomes related to excellence gaps. The ability to highlight any such discrepancies is a major improvement in this line of research and also explains why states may perform quite differently across the two iterations of the report.

Figure 1: Project Logic Model

Figure 2: Indicators Used in This Report. Items in bold are new to this report in 2018.

Methods and Limitations

Project staff compiled a database to record each variable for all 50 states plus the District of Columbia. Data were drawn from multiple online and documentary sources (Appendix A).8 When critical data were missing, project staff contacted state education agency (SEA) staff directly, and if that effort was unsuccessful, we used data from earlier versions of the targeted data sets.

Much of the policy data are self-reported by SEA officials on various surveys. Self-reported data have well-known limitations, but the consistency of responses across the past few administrations of the surveys, in combination with random checks of the responses by the research team, provide a level of confidence in the reliability and validity of those data.

The biggest limitation of this report is the lack of available data on the education of advanced students, especially as it relates to excellence gaps and low-income students and their families. Many of the indicators recommended by the expert panel are not readily available, and in some cases the data of interest do not appear to be publicly available.9

In the following section, we describe our grading approach and our findings of the extent to which states have implemented these policies and achieved these desired outcomes.

Grading System

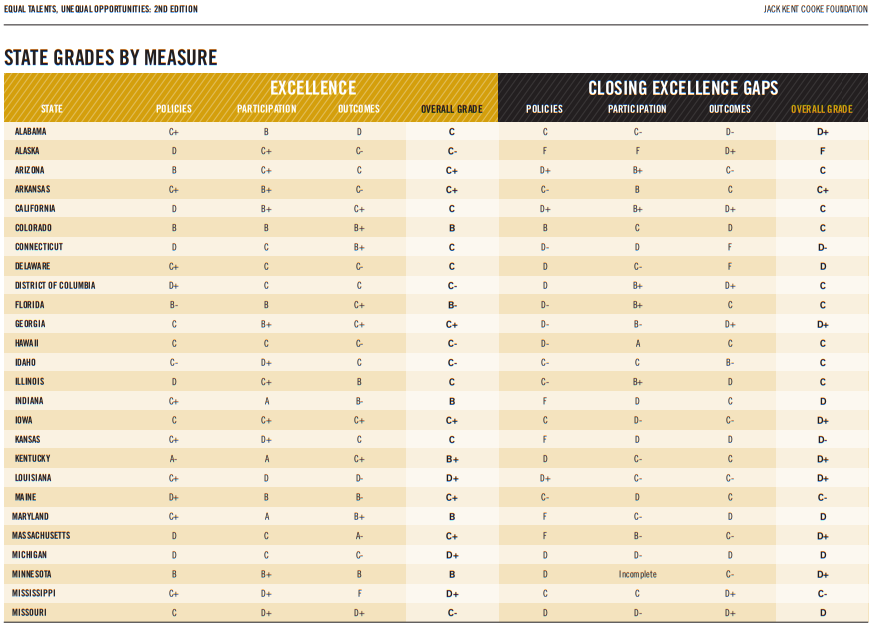

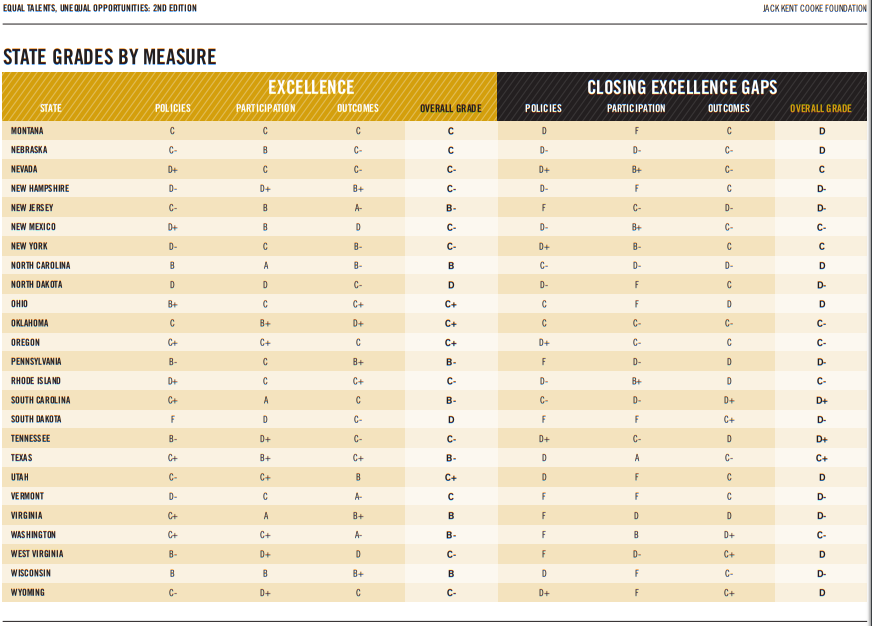

Every state receives eight grades in this report: two overall grades, and six measure grades (Figure 3). The first two grades measure broadly the extent to which we observe progress in states:

- Excellence Grade: the extent to which states promote and achieve learning for their high-ability students

- Closing Excellence Gaps Grade: the extent to which states ensure that low-income students have equal access to advanced learning opportunities and are equally likely to achieve high levels of academic excellence as other students

To maximize this report’s usefulness, we calculate six additional measure grades to assess each state’s policies, participation, and outcomes as they relate to excellence and excellence gaps.

Excellence Measures:

- Policies that support excellence

- Participation rates of all students in advanced learning opportunities

- Outcomes of all students at the advanced level

Excellence Gap Measures:

- Policies that help close excellence gaps

- Participation rates of low-income students in advanced learning opportunities

- Outcomes of low-income students at the advanced level

Figure 3: Grading System

Results

Supporting Excellence

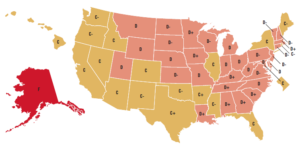

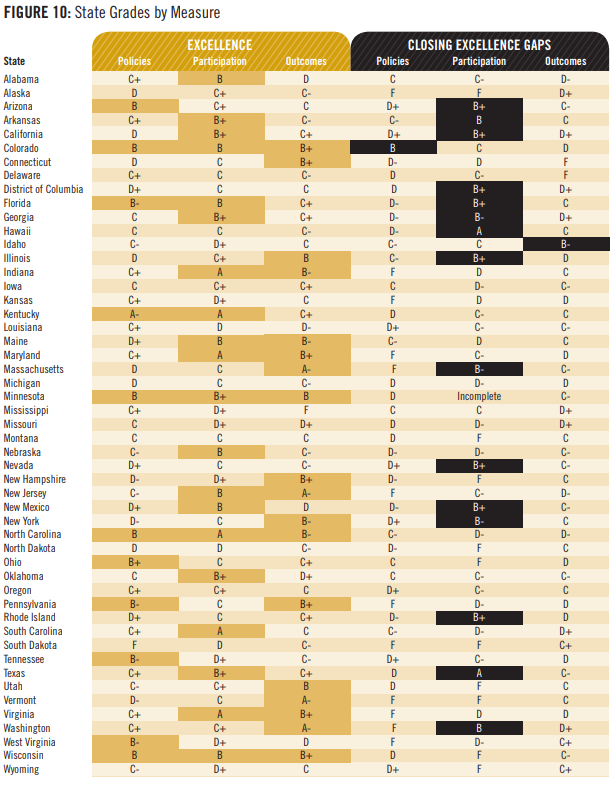

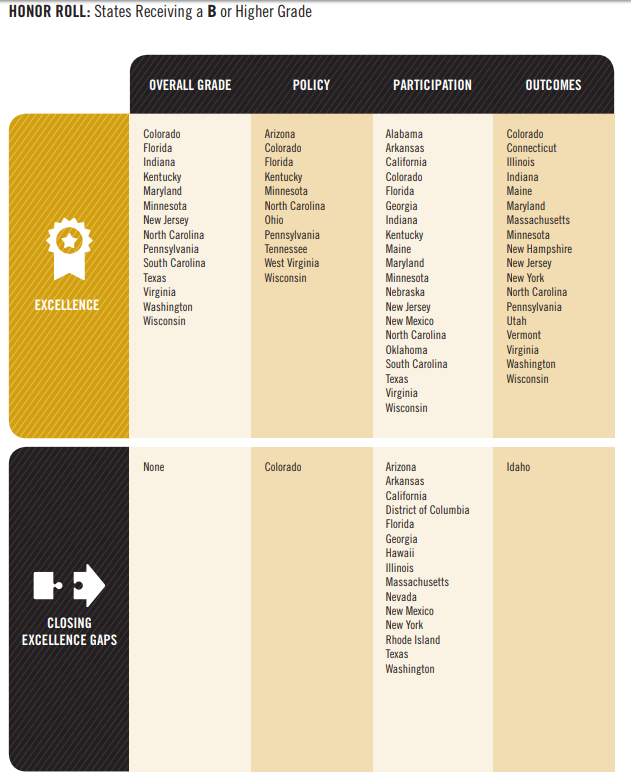

Figure 4 presents the state grades for EXCELLENCE, i.e., the extent to which states promote and achieve learning for their high-ability students. Fourteen states receive a grade of B or better for their work supporting excellence. Four of these states (Colorado, Minnesota, North Carolina, and Wisconsin) had strong results across all three grading areas — policies, participation, and outcomes (Figure 10). The remaining states had more mixed results. Nationwide, the average excellence grade was a C.

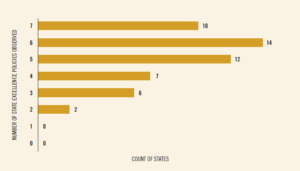

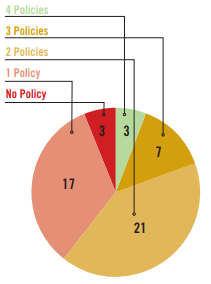

Since our first report, we see modest improvement among states implementing policies that support excellence. All states have at least two of the seven policies intended to promote excellence in place; 10 states have all seven (Figure 5). The most frequently observed policy was “identifying and serving advanced students,” now required in 33 states (up from 32 in 2015). On average states had five of the seven policies. Of course, a raw count of policies does not account for the strength of policies. Strength and degree of implementation are considered in the detailed results presented later in this report.

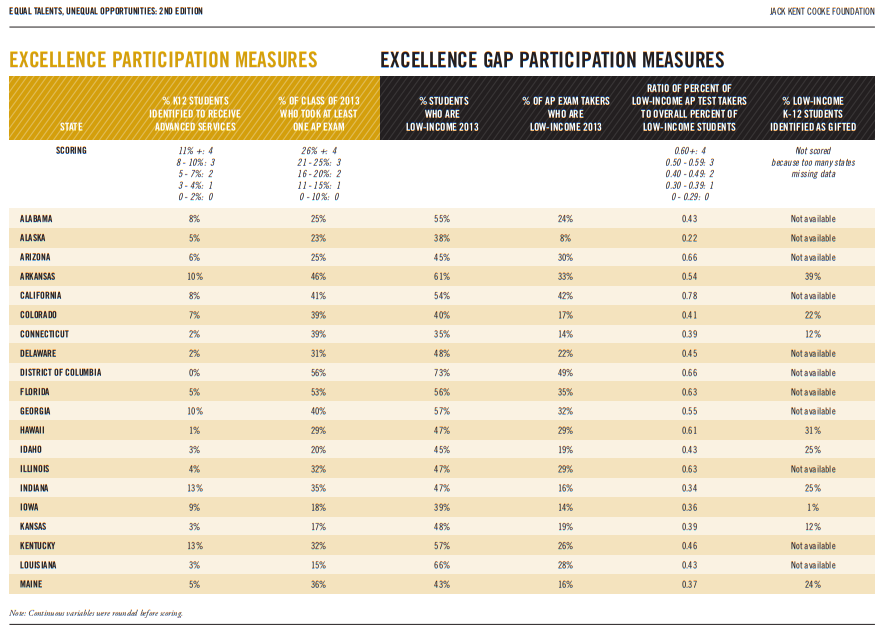

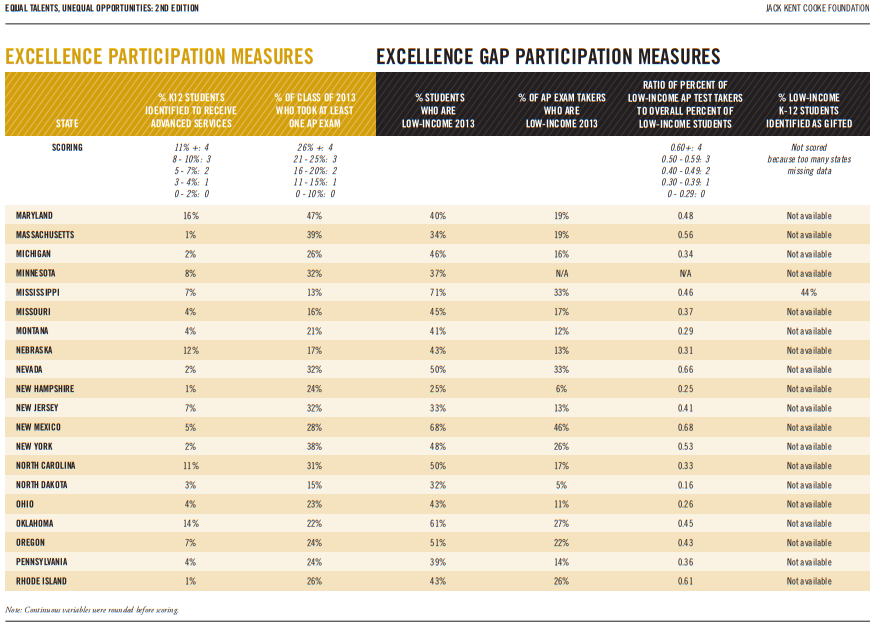

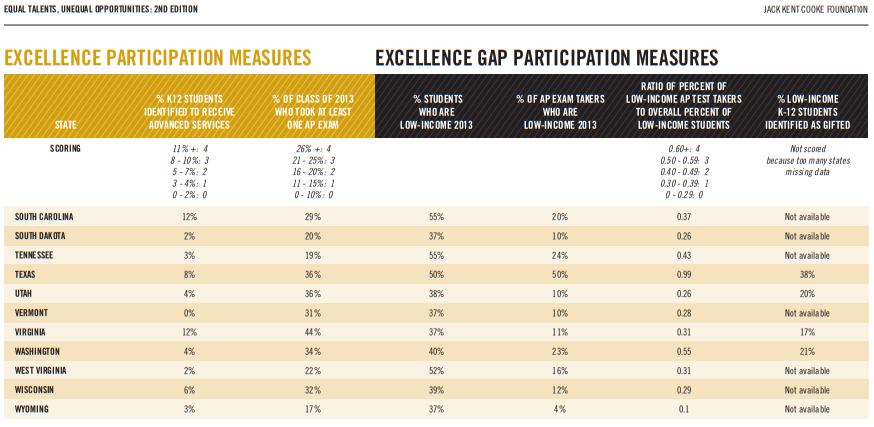

New to this year’s report are participation indicators. In 2015, participation data were difficult to find. They proved equally difficult in the preparation of the current report, and we relied on proxy variables to provide at least some sense of how participation compares among states. We included two measures of overall participation for excellence: identification for gifted services, and participation in Advanced Placement (AP) courses. Nationwide, on average 6 percent of students are identified for gifted services. Participation is higher for AP courses; on average 29 percent of states’ high school graduates took an AP Exam during high school.

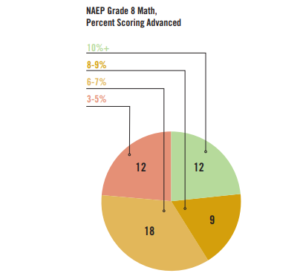

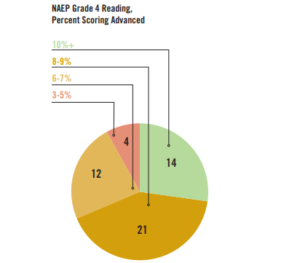

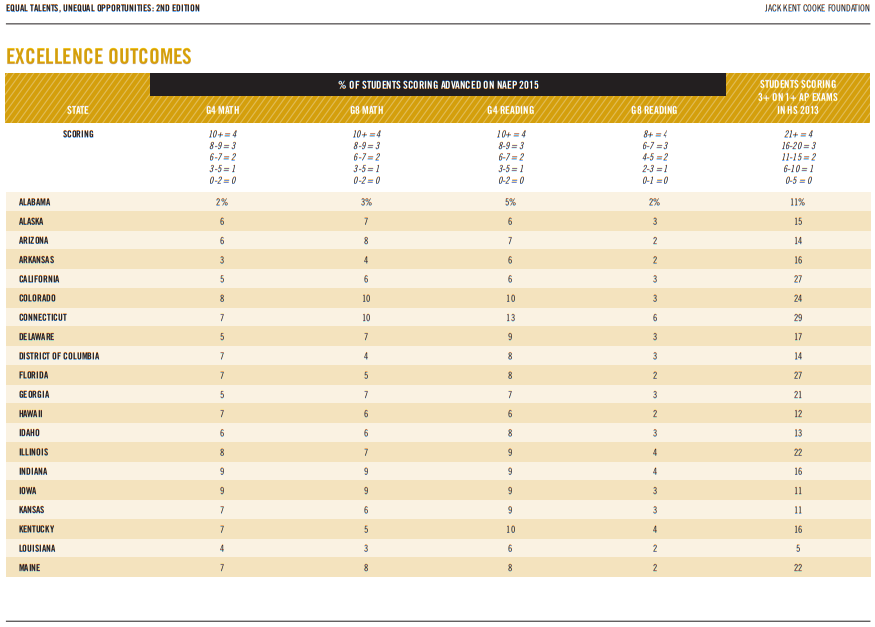

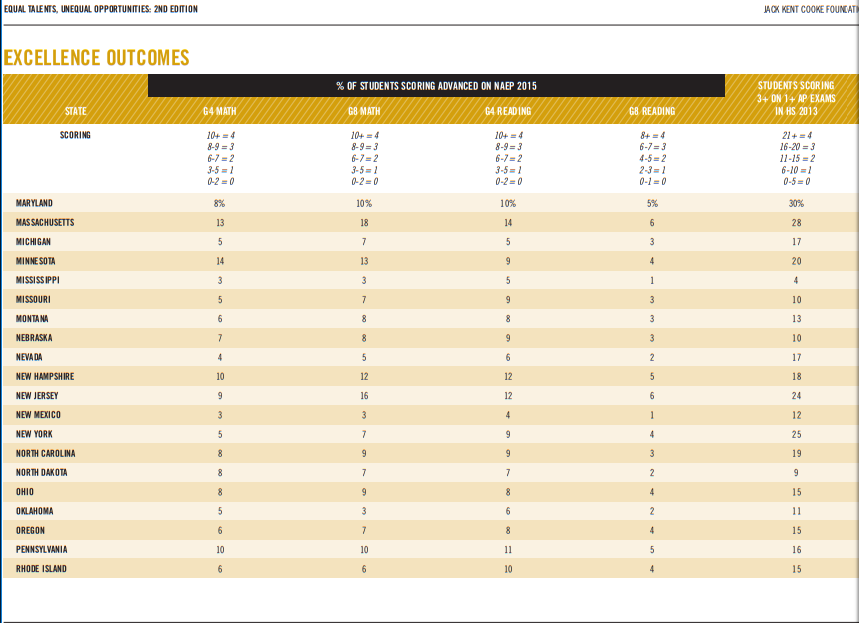

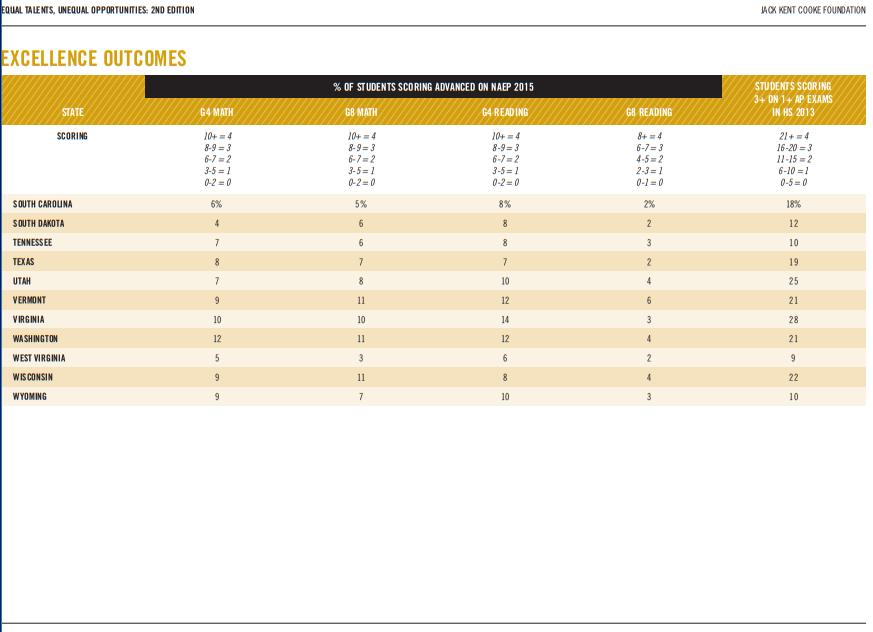

We included the same five outcome measures as the first report: grades 4 and 8 math and reading, and high school AP test results. Outcomes are mixed. Some states have strong outcomes, with over 10 percent of elementary or middle school students scoring “advanced” on the National Assessment for Education Progress (NAEP). The exception is grade 8 reading, where very few students seem to excel. Compared to two years ago, fewer states report high outcomes in grades 4 and 8; one more state scored highly on the AP measure.

Overall, the excellence measures of this report paint a mixed picture of progress when it comes to supporting learning at the advanced level. States are beginning to require supportive policies, students are participating, and outcomes in 18 states are high.

Figure 4: State Grades for Excellence. The extent to which states promote and achieve learning for their high-ability students.

Figure 5: Number of Policies States Have Implemented to Support Excellence

Closing Excellence Gaps

The picture is starkly different when we examine EXCELLENCE GAPS. Not a single state in the nation received a good grade for closing excellence gaps (Figure 6). In fact, the average grade across the nation was a D+.

The consistently low grades for excellence gaps — in all 50 states and the District of Columbia — stems from a lack of pertinent policies and from abysmally poor advanced learning participation and outcomes among states’ low-income students relative to their peers (Figure 10). Indeed we saw only one state (Colorado) receive a B for policies, and one (Idaho) receive a B for outcomes.

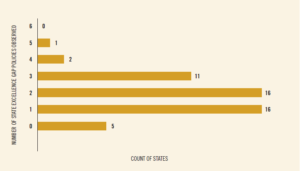

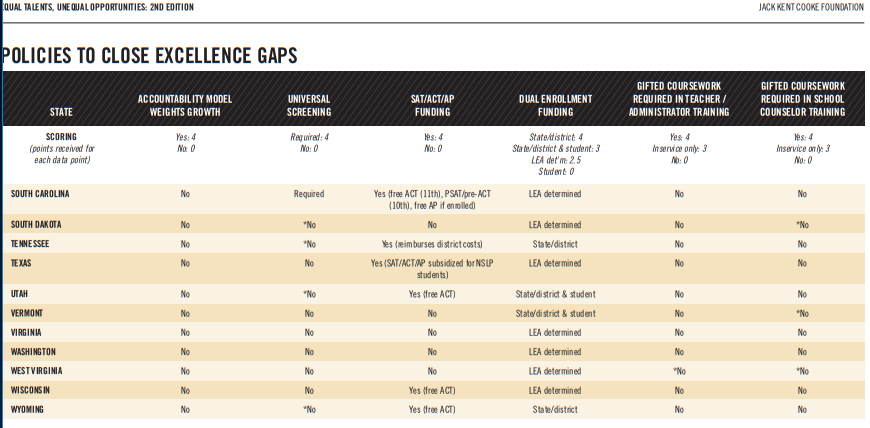

Six excellence gap policies were examined, policies that remove financial or administrative barriers that might keep low-income students from accessing advanced learning opportunities. No state has all six policies in place (Figure 7). Colorado alone has five of the six; only 13 other states have even half of the policies in place. On average states have mandated only two of the six policies.

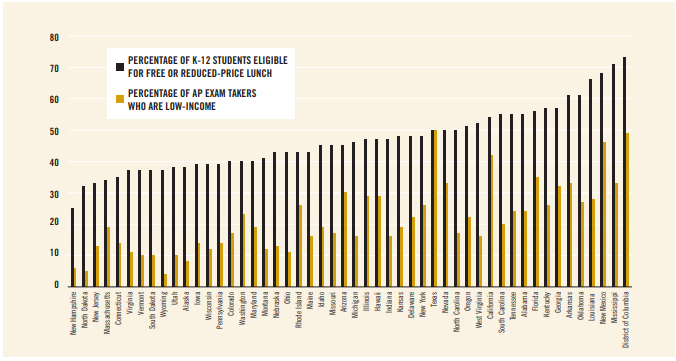

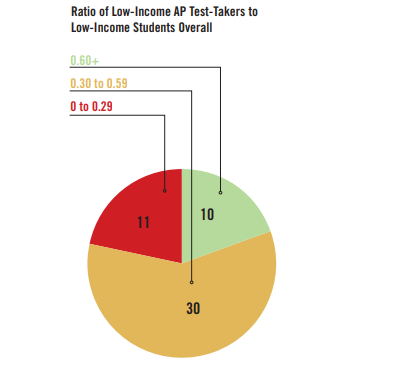

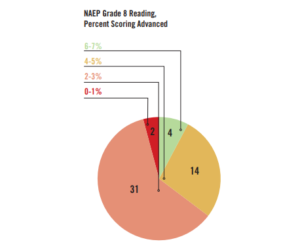

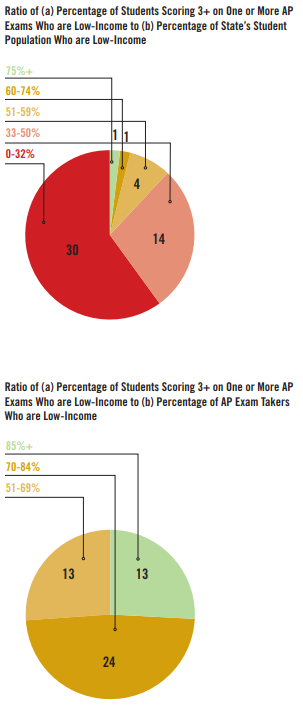

To measure participation of low-income students in advanced learning, we sought to include two indicators: the percentage of low-income students identified as gifted, and the percentage of those who take AP tests. Unfortunately, the U.S. Department of Education does not report on gifted education by socioeconomic status. Thus we only included a single participation measure, and the results are mediocre: in only 10 states are low-income students even somewhat represented among AP exam takers (Figure 9, Page 12). Texas alone has equal representation of low-income students among its AP exam takers as its student body generally. This may be attributable to Texas’ robust AP subsidy program, which provides test fee subsidies to students and reimbursement of teacher training costs.

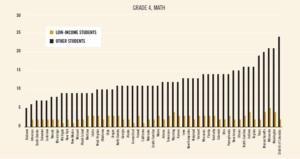

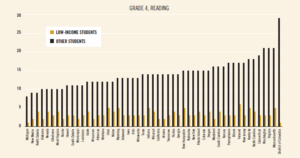

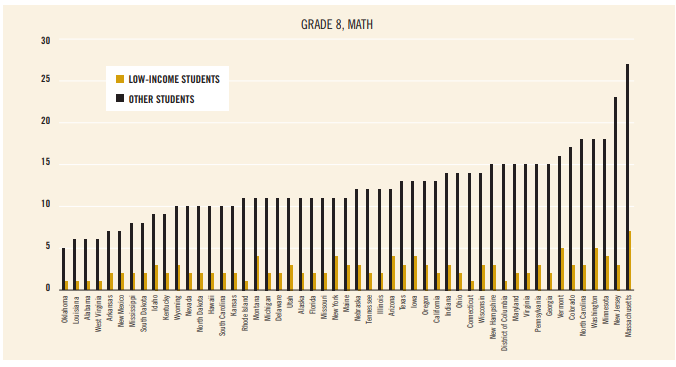

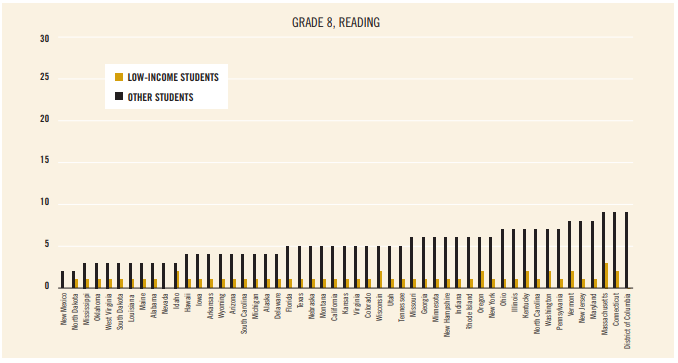

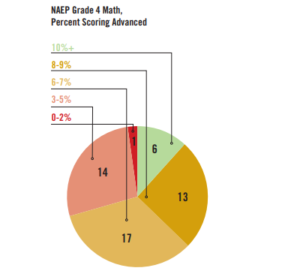

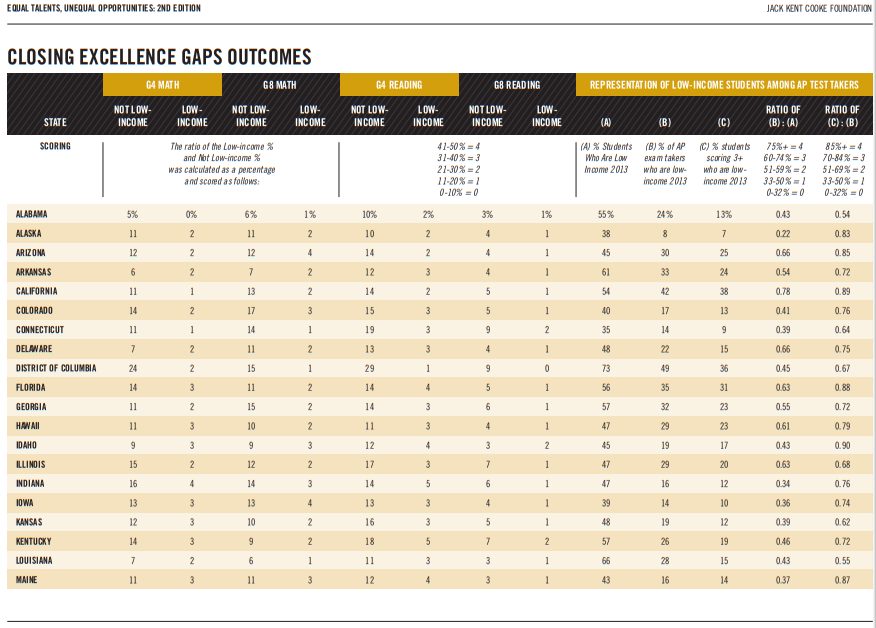

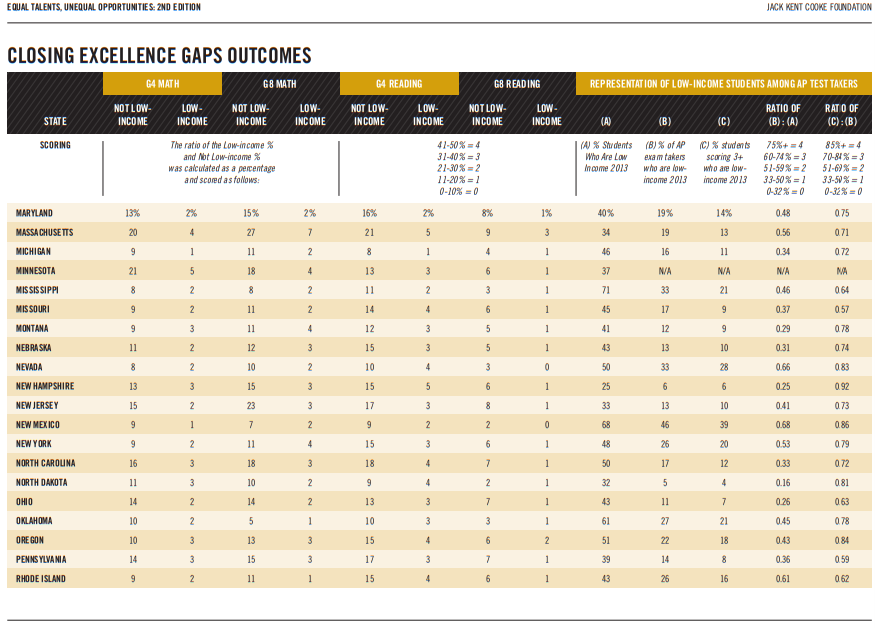

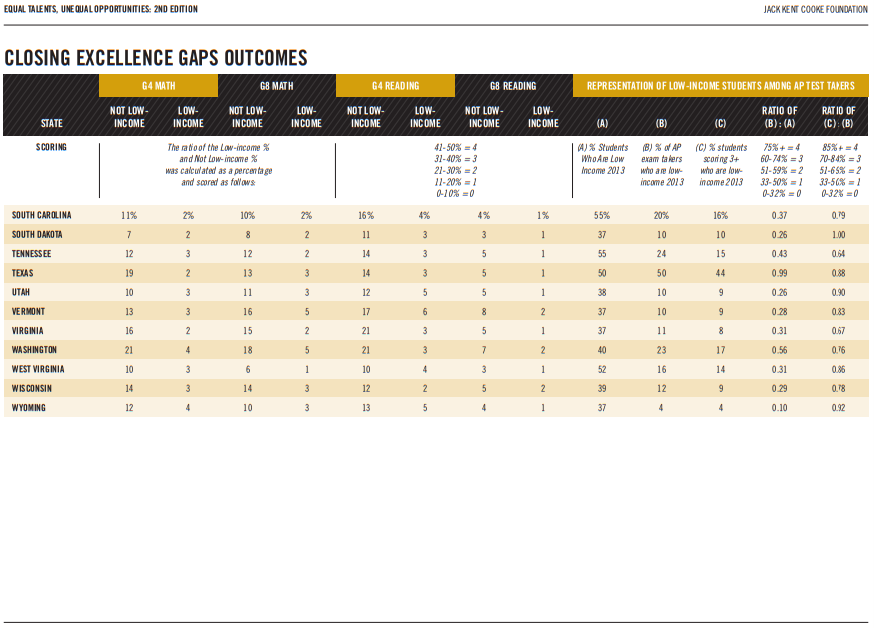

Results are even worse for outcomes. Every state in the nation has excellence gaps — in grade 4, grade 8, and high school; in math and in reading (Figure 8). These excellence gaps range in size. In grades 4 and 8, in math and reading, we observe state excellence gaps as small as 1 percent (North Dakota, grade 8 reading) and as large as 28 percent (District of Columbia, grade 4 reading). In other words, in the District of Columbia, only 1 percent of low-income students score at the advanced level in grade 4 reading, while 29 percent of other students do so!

These examples highlight a stark reality: the size of excellence gaps is driven primarily by how well other students perform, relative to their low-income peers. In the case of excellence gaps, a rising tide does not raise all boats. Regardless of how well other students do, the percentage of low-income students scoring at the advanced level hovers around 2 to 3 percent, and is never higher than 7 percent (Massachusetts, grade 8 math).

Figure 6: State Grades for Closing Excellence Gaps. The extent to which states ensure that low-income students have equal access to advanced learning opportunities and are equally likely to achieve high levels of academic excellence as other students.

Figure 7: Number of Policies States Have Implemented to Close Excellence Gaps.

Figure 8a: Outcome Excellence Gaps, Grade 4, Math and Reading. Source: Percentage of students scoring at the “Advanced” level. National Assessment of Education Progress, 2015.

Figure 8b: Outcome Excellence Gaps, Grade 4, Math and Reading. Source: Percentage of students scoring at the “Advanced” level. National Assessment of Education Progress, 2015.

Figure 8c: Outcome Excellence Gaps, Grade 4, Math and Reading. Source: Percentage of students scoring at the “Advanced” level. National Assessment of Education Progress, 2015.

Figure 8d: Outcome Excellence Gaps, Grade 4, Math and Reading. Source: Percentage of students scoring at the “Advanced” level. National Assessment of Education Progress, 2015.

Data Results and Indicators

There is hope, though. When we look at each state across the six measure areas (i.e., policies, participation, and outcomes related to either excellence or closing excellence gaps), we see tremendous variation. Thirty-eight states received a B or higher in at least one measure (Figure 10). Figures 11 through 16 present the national results for each measure, and Appendix B contains state-by-state results. On every indicator, at least some states are doing well. So although practices and results range widely among and within states, we see signs of progress.

Figure 9: Participation Excellence Gaps, AP Exam Takers. Source: The 10th Annual AP Report to the Nation, College Board, 2014.

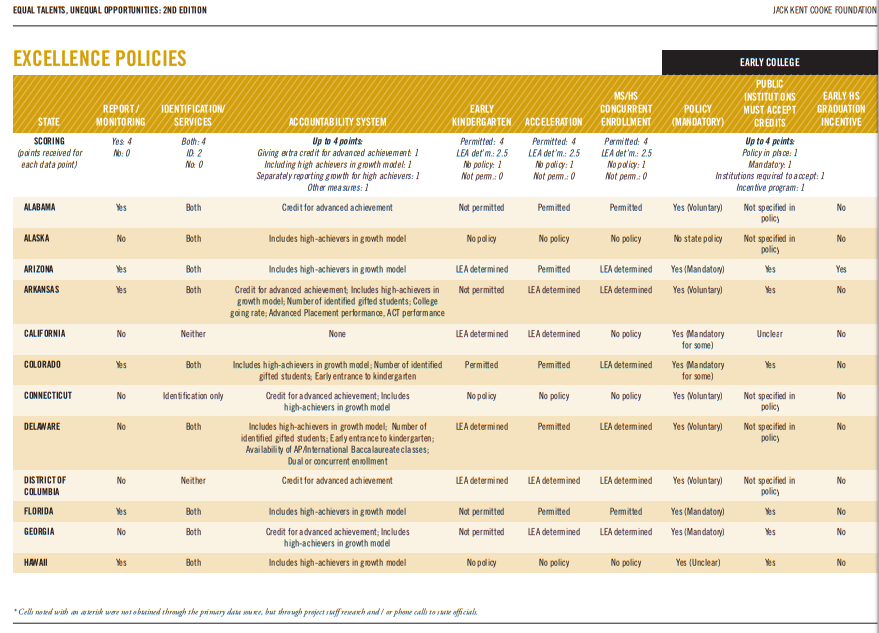

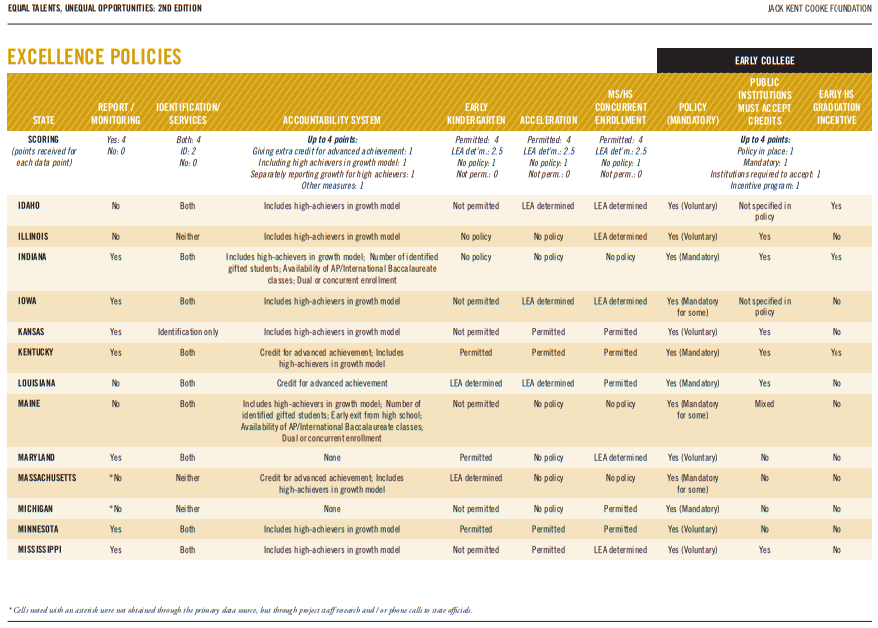

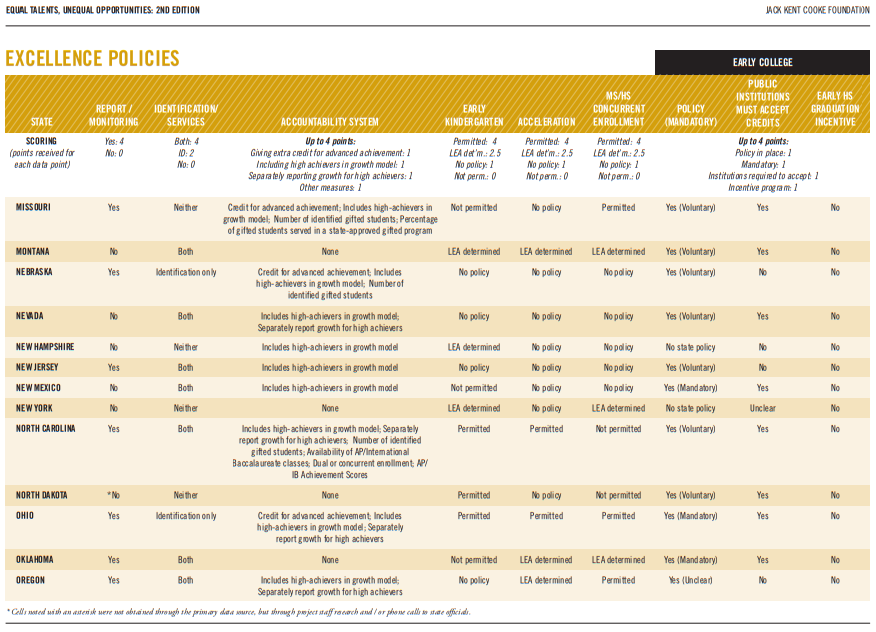

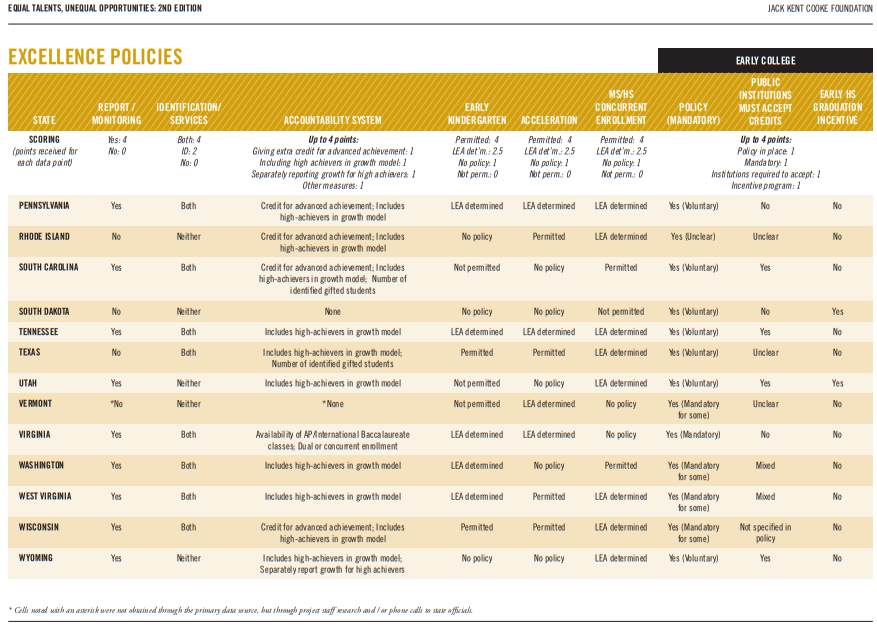

Figure 11: Policies Promoting Excellence - To what extent do state policies support and facilitate advanced learning for all students?

Excellence Policy Indicator 1:

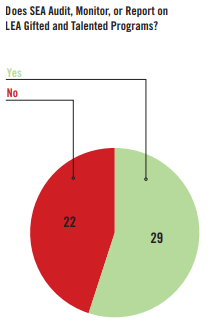

State produces an annual report on gifted and talented (G&T) programs or monitors/audits local G&T programs

A state that emphasizes advanced education should have some form of state-level monitoring for related Local Education Agency (LEA) programs and interventions. States received full credit on this indicator if they reported either monitoring/ auditing LEA gifted education services or preparing an annual report on the “state of the state” regarding advanced education.

Progress since 2015: Slightly Positive. One additional state monitors, audits, or reports on advanced education.

Source: NAGC State of the States Report, 2014-2015 (“NAGC report”)

Excellence Policy Indicator 2:

State mandates identification or services for identified advanced learners

Requiring identification and service delivery for advanced students is an indicator of the value a state places on academic excellence, including for low-income students who may be attending schools in which proficiency is valued more highly than advanced performance. States received full credit on this indicator if they require services (i.e., with identification implied), and partial credit if they only require identification.

Progress since 2015: Slightly Positive. One more state has added requirements for identification and services.

Source: NAGC report

Figure 11 (cont'd): Policies Promoting Excellence

Excellence Policy Indicator 3:

State accountability system includes measures of advanced learning and excellence

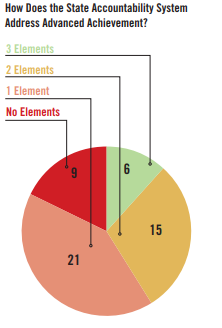

State K–12 accountability systems drive the priorities of our schools, yet they traditionally focus only on low-achieving students and minimum competency. The inclusion of indicators representing high levels of academic performance is a strong, formal statement of the importance of advanced education, especially when those indicators give schools and districts credit for helping low-income students achieve at high levels. We used four characteristics of each state’s accountability system to derive an accountability excellence score: whether the system gives credit for advanced achievement; includes high achievers in its growth model; separately reports growth for high achievers; and includes other indicators of excellence (e.g., number of identified gifted students, AP participation and outcomes, availability of AP/IB classes, dual/concurrent enrollment, career/ technical education, graduation rates, college-going rates, SAT/ACT performance). States received full credit if all four characteristics were in place.

New indicator.

Source: Fordham Institute report, “High Stakes for High Achievers” (“Fordham report”), 2016; state accountability plans as described in policy documents

Excellence Policy Indicator 4:

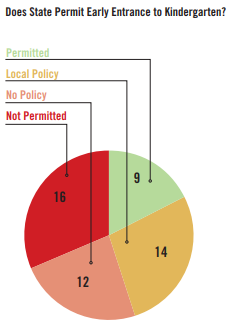

State policy allowing early entrance to kindergarten

Children should be able to enter kindergarten when they are intellectually ready to do so, not only when their birthday falls on the correct side of an arbitrary cut-off date. This may be especially important for low-income students, who may benefit from additional educational supports and social services that are available in K–12 schools. States were given full credit on this indicator if they have a state policy that allows early entrance to kindergarten, partial credit if they leave such policy decisions to local districts, slight credit if they have no applicable policies, and no credit if they expressly forbid it.

Progress since 2015: Mixed. The number of states who forbid early entrance to kindergarten has decreased from 20 to 16, but the number of states with formal policies permitting early entrance to kindergarten has decreased from 11 to 9. As a result, there has been a shift towards no policy or local control policies.

Source: NAGC report

Figure 11 (cont'd): Policies Promoting Excellence

Excellence Policy Indicator 5:

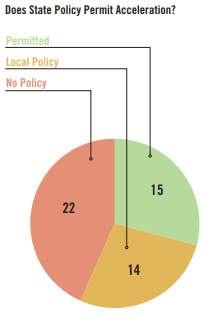

State acceleration policy

Students should be able to move through the K–12 system at their own pace. For some students, this pace can be considerably accelerated, and the benefits of academic acceleration are well documented.10 Having a state acceleration policy both sends a strong message that acceleration is valued and permissible and provides a policy lever for educators and parents to use when they encounter anti-acceleration bias. States were given full credit on this indicator if they have a state acceleration policy, partial credit if they leave such policy decisions to local districts, slight credit if they have no applicable policies, and no credit if they expressly forbid it.

Progress since 2015: Positive. The number of states requiring all schools to allow acceleration has increased from 9 to 15. Delaware, Florida, Kentucky, Mississippi, Rhode Island, and Wisconsin have all added policies permitting acceleration.

Source: NAGC report

Excellence Policy Indicator 6:

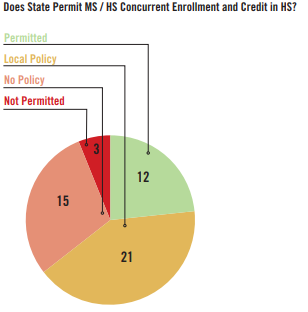

Middle school / high school concurrent enrollment and credit in high school

Having access to high school courses while attending middle school provides students with challenging coursework that their school may not otherwise be able to offer. This may be especially important for low-income students, who are more likely to attend schools with limited resources, therefore restricting advanced options in the middle school. Students who take high school coursework while in middle school should also be able to get high school credit, allowing them to move through the K–12 system at a more appropriate pace and experience greater enrichment opportunities when they enter high school. States were given full credit on this indicator if they have policies that specifically allow middle school / high school dual enrollment, and if the state allows for such enrollment to result in the granting of high school credit. States received partial credit if they leave such policy decisions to local districts, slight credit if they have no applicable policies, and no credit if they expressly forbid it.

Progress since 2015: Mixed. While the number of states forbidding concurrent enrollment dropped by three, five fewer states have state-wide policies permitting it.

Source: NAGC report; Acceleration Institute

Figure 11 (cont’d): Policies Promoting Excellence

Excellence Policy Indicator 7:

Early college / dual enrollment policies

Allowing talented students to move through high school at an accelerated pace is both educationally desirable and potentially cost saving. Some states encourage early graduation and entrance into college, and others support dual enrollment programs that allow students to complete college coursework while still in high school. A robust early college / dual enrollment system has the potential to accelerate achievement for many students. We used four characteristics of each state’s policies to derive this score: whether the state has a dual enrollment policy in place; whether dual enrollment is voluntary or required in every high school in the state; whether public postsecondary institutions are required to accept students’ dual enrollment credits; and whether the state has an early graduation incentive policy. Only three states have all four policies in place: Indiana, Kentucky, and Arizona.

New indicator.

Source: Education Commission of the States and Jobs for the Future reports (“ECS reports”); state policy documents

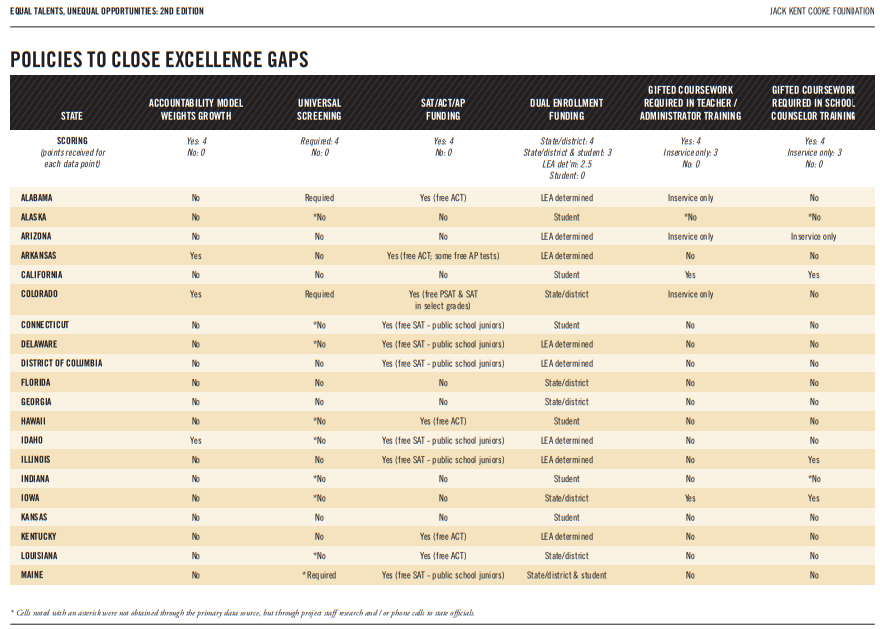

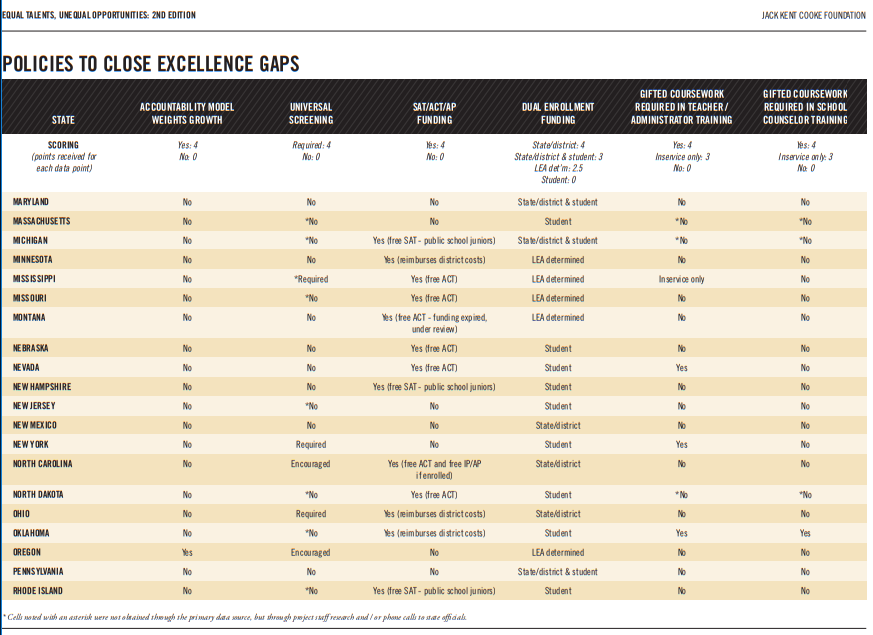

Figure 12: Policies to Close Excellence Gaps - To what extent do state policies support and facilitate advanced learning for all students regardless of student income?

Excellence Gap Policy Indicator 1:

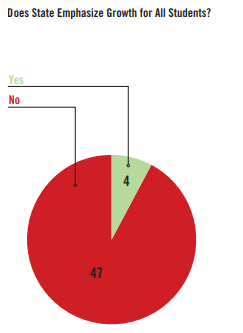

Prominence of growth for every student in state accountability system

A state accountability system may encourage schools to focus on excellence without incentivizing educators to address excellence gaps. For this indicator, states received full credit for ensuring that at least half of a school or district’s accountability rating is based on growth for all students (as opposed to growth for just lower-performing students).

New indicator.

Source: Fordham report

Excellence Gap Policy Indicator 2:

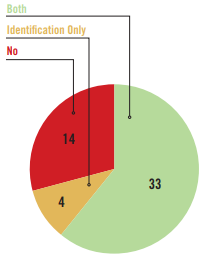

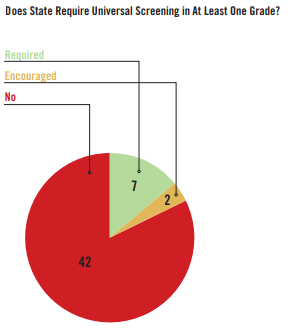

State policy for universal screening

In the three years since our last report, research support for universal screening has significantly increased. Universal screening is the practice of putting every student in a targeted grade through the identification process for gifted education and talent development programs. Research provides evidence that non-universal screening tends to exclude low-income students, therefore increasing excellence gaps.11 We initially intended this indicator to represent whether a given state offered dedicated funding for universal screening, but only one state does so (Colorado). A handful of states do require or encourage universal screening and financially support its implementation through a range of other mechanisms. The indicator was modified so states that require universal screening in at least one K–12 grade received full credit, or partial credit for “encouraging” it.

New indicator.

Source: State policy documents; NAGC report

Figure 12 (cont’d): Policies to Close Excellence Gaps

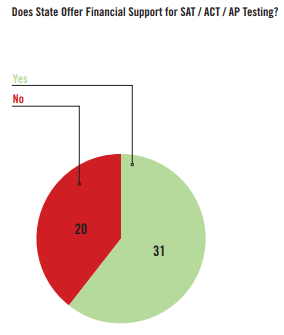

Excellence Gap Policy Indicator 3:

Financial support for SAT / ACT / AP testing

The fees associated with AP tests and college entrance examinations can be a major obstacle for low-income students. Many states have recognized this barrier to excellence and have enacted policies that provide at least some relief from fees associated with these “gatekeeper” tests. States received full credit for providing financial assistance for the costs associated with at least one test.

New indicator.

Source: NAGC report; state policy documents

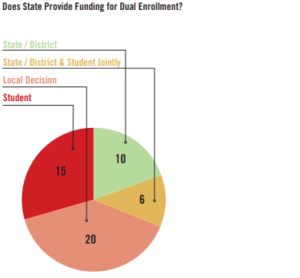

Excellence Gap Policy Indicator 4:

Financial support for dual enrollment costs

Dual enrollment may be an effective strategy for promoting advanced achievement for high school students, but fees and tuition costs associated with dual enrollment may serve as barriers that grow excellence gaps. States received full credit for having policies that relieve students of this burden entirely, partial credit for policies that require students to cover some of the costs or that cede the decision to local control, and no credit for placing the whole financial burden on students and their families.

New indicator.

Figure 12 (cont’d): Policies to Close Excellence Gaps

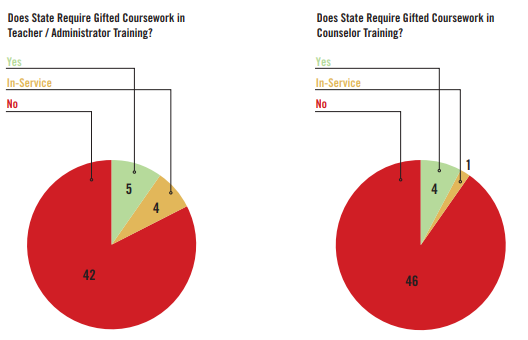

Excellence Gap Policy Indicators 5 and 6:

Gifted coursework required in teacher, administrator, and counselor training

If educators are not exposed to material on the education of high ability students, it is unlikely that those educators will be sensitive to the needs of those students, especially those who are low-income. For indicator 5, states were given full credit on this indicator if they require coursework on gifted and talented learners in pre-service training or administrator training; for indicator 6, full credit if they require coverage in school counselor training. Partial credit was awarded on indicator 5 if gifted coursework is required as part of in-service teacher training, as in-service training is often less rigorous than pre-service training.

Progress since 2015: Positive. The number of states requiring at least one of these groups to take coursework on gifted learners has risen from 3 in 2015 to 10 in 2018.

Source: NAGC report

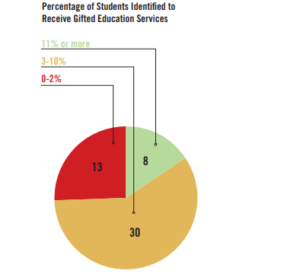

Figure 13: Excellence Participation - To what extent do students participate in advanced learning?

Excellence Participation Indicator 1:

Percentage of students identified to receive gifted education services

The percentage of students receiving services via gifted education is an indicator of the extent to which a state is promoting educational excellence. Each state received full credit for having 11 percent or more of its students identified as gifted and talented, with partial credit for 3 to 10 percent, and no credit for 2 percent or less.

New indicator.

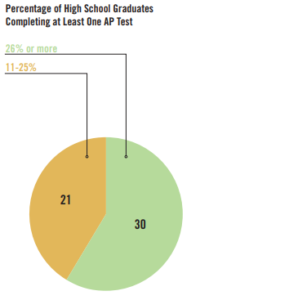

Excellence Participation Indicator 2:

Percentage of graduates who took at least one AP test

Similarly, the rate at which states’ high school graduates take AP tests is an indicator of participation in rigorous programs at the high school level. States received full credit for AP test-taking rates of 26 percent or more, partial credit from 11 to 25 percent, and no credit for 10 percent or less.

New indicator.

Figure 14: Excellence Gap Participation - To what extent do low-income students participate in advanced learning?

Excellence Gap Participation Indicator 1:

Representation of low-income students among AP test takers

In schools with small excellence gaps, the percentage of low-income students who take at least one AP test should be similar to the percentage of low-income students in the school system. States received full credit on this indicator if the ratio of low-income test-takers to low-income students was 0.60 or higher, partial credit for 0.30 to 0.59, and no credit for 0.29 or less. For example, a state with 60 percent lunch assistance overall and 30 percent of AP test-takers receiving lunch assistance has a ratio of 0.50. A state with no underrepresentation would have a ratio of 1.0.

New indicator.

Excellence Gap Participation Indicator 2:

Percentage of low-income students identified as gifted

We intended to include an indicator representing the percent of each state’s gifted education population that are from low-income backgrounds. However, the U.S. Department of Education’s Office of Civil Rights (OCR) only collects data on student race and not socioeconomic status, and very few states report such data. Several report that the data are not available or not collected. This is a major limitation in the country’s education data and should be addressed by all states. This indicator was not factored into the ratings in this report, but we include the spotty data in the summary data tables (see Appendix B) as an encouragement to states and OCR to address this issue.

New indicator.

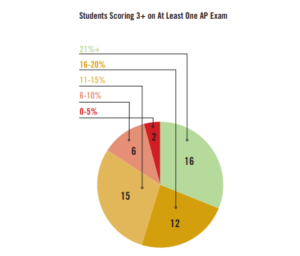

Figure 15: Excellence Outcomes - To what extent do students reach advanced levels of performance?

Excellence Outcome Indicators 1-5:

Advanced achievement for all students

A key outcome is the percent of public school students who perform academically at advanced levels. We included indicators on student performance at several levels: NAEP math and reading data for grade 4 and grade 8, and AP exam data to represent high school achievement. Although we collected grade 4 and 8 NAEP science data, the advanced performance levels on science were so low among all states that providing a non-punitive rating would have been impossible.

To receive full credit on these indicators, state data needed to reflect:

- At least 21 percent of students scored 3 or higher on at least one AP exam

- At least 10 percent scored in the advanced range (grade 4 and 8 math, grade 4 reading)

- At least 8 percent scored in the advanced range (grade 8 reading).12

The four NAEP achievement indicators contributed to two-thirds of each state’s excellence outcome grade, with AP performance representing the remaining third.

Progress since 2015: Negative in grades 4 and 8. Fewer states this year report high percentages of students reaching the advanced level than two years ago. Positive in high school. One more state scored highly on the AP measure.

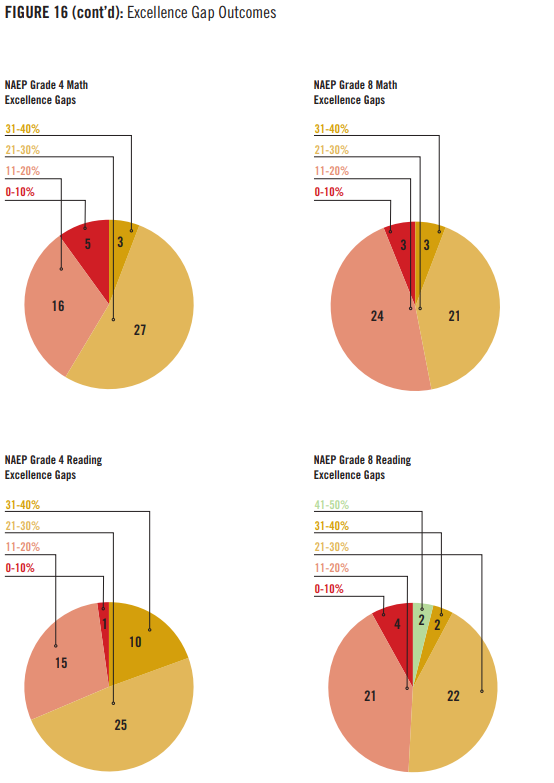

Figure 16: Excellence Gap Outcomes - To what extent does the performance of low-income students differ from their peers at advanced levels?

Excellence Gap Outcome Indicators 1-6:

Advanced achievement for low-income students versus non-low-income students

High levels of academic progress do not necessarily mean that all student subgroups share the same levels of accomplishment. If a state has a relatively large percent of students scoring advanced on NAEP, but most of those students are not low-income, the state is not promoting educational excellence for all.

To receive full credit on these indicators, state data needed to reflect three conditions:

- The percent of students scoring 3 or higher on an AP test who were low-income was at least 75 percent of the level of low-income students in the state

- The percent of students scoring 3 or higher on an AP test who were low-income was at least 85 percent of the level of low-income students who took an AP test

- A state’s NAEP data showed that the percent of low-income students scoring advanced had to be at least 41 percent of the percent of non-low-income students scoring advanced (grade 4 and 8 math, grade 4 and 8 reading)

Progress since 2015: Mixed. The grade 8 scores are slightly improved, while the grade 4 scores are worse. The AP measures are new this year.

Source: NAEP, AP report

Note: Minnesota is missing its data on AP participation, thus the two AP charts sum to 50, not 51.

Figure 16 (cont'd): Excellence Gap Outcomes

Promising Examples

In the 2015 report, we highlighted Minnesota, Ohio, and Pennsylvania as three states leading the way in implementation of pro-excellence policies. Based on the current analyses, these three states continue to innovate and serve as examples to other states.

SEVERAL OTHER STATES EMERGED AS LEADERS IN 2018:

Colorado was the top scoring state in this year’s analysis, with an above average grade for pro-excellence policies (B) and the highest rating in the nation for excellence gap policies (B). The state has both identification and service mandates, and the state monitors and reports on gifted education programming. Colorado allows early entrance to kindergarten and has a state acceleration policy. Concurrent enrollment policy for middle school students is left up to local districts, but other dual enrollment policies (primarily focused on high school students) are relatively strong. The state’s education department also provides extensive resources for local districts and educators. But what truly sets Colorado apart from other states are its excellence gap policies: state funding for dual enrollment, universal screening, and high-stakes tests (free PSAT to all public school students in grade 10 and free SAT to all public school juniors). Additionally, the state accountability system heavily weights growth for all students, and teachers are required to receive relevant in-service training. In addition to above-average state department of education leadership and support, the state has a strong state association for gifted and talented students and considerable university expertise.

Kentucky had the highest grade (A-) for excellence policies in the nation. Although its excellence gap policies are in need of improvement, its excellence policies are exemplary. They include state department reporting and monitoring; identification and service mandates; and state policies on early kindergarten entrance, acceleration, and middle school concurrent enrollment. In addition, Kentucky has among the strongest dual enrollment policies in the country, including an early graduation / early college incentive program. The state also has considerable university expertise and a strong state association for gifted education. The well-regarded Prichard Committee, a bipartisan group that strongly influences education reform in the commonwealth, has also turned its attention recently to issues of advanced achievement and excellence gaps.

Wisconsin has above average excellence policies, participation, and outcomes (but as with Kentucky, less impressive excellence gap indicators). Particular policy strengths include identification and service mandates, state monitoring, and policies allowing early entrance to kindergarten and acceleration. In addition to strong state department of education leadership and support, the state has a strong state association for gifted and talented students.

Arizona has above-average dual enrollment policies, and a mandate and state department monitoring of programs. The state also has strong state department of education leadership and support and has begun working topics related to excellence and excellence gaps into their professional development and leadership offerings for educators.

North Carolina has many of the strengths of other states that scored well for excellence policies, but the state is unique in the focus of its accountability system on advanced achievement. The system currently includes indicators for the number of identified gifted students, availability of AP and International Baccalaureate (IB) classes, dual enrollment, and AP / IB test results. This balance of excellence indicators focused on both participation and outcomes is uncommon and laudable. The state also has considerable university expertise, strong state department of education leadership, and a strong state association for gifted education. Recent media attention to income-based excellence gaps has led to public and policymaker discussions that appear likely to lead to improved policies and practices in this area.13

What We Learned

FROM OUR REVIEW OF THE DATA THIS YEAR,

WE DRAW SEVERAL CONCLUSIONS:

- Policy support for advanced learning is improving, but is still incomplete and haphazard. All states can do more to support advanced learning.

We examined 13 policies for this report: 7 for excellence, 6 for excellence gaps. Collectively, the 50 states and the District of Columbia report a range of policy positions and accountability measures for advanced learning. While no state has all 13 policies in place, Colorado comes close (with 12). The average is 7. We observe very slight changes since 2015, with more states requiring identification, monitoring, and acceleration. Still, the change is incremental. There is still tremendous room for improvement.

2. States are more likely to have policies that support excellence overall, rather than those that support the closing of excellence gaps.

On average states have implemented 5 of the 7 excellence policies, but only 2 of the 6 excellence gap policies. While 84 percent of states have more than half of the desired excellence policies in place, only 6 percent (3 states!) have more than half of the excellence gap policies in place. These areas of attention are simply missing from state radars, and our low-income students pay the price.

Since we concluded data collection for this report, several states and school districts have implemented new policies and strategies to address excellence gaps. In particular, Washington is becoming a leader on these issues with an approach combining accountability and support for districts as they identify gifted low-income and minority students. Illinois passed several legislative initiatives into law that directly support the identification and education of talented low-income students. A number of districts, such as Pinellas County in Florida, are implementing strategies such as universal screening with some evidence of success. These recent activities are further evidence of increasing momentum toward attacking this important policy issue. Other states should follow suit.

3. Participation rates — both generally and for low-income students — are strong in some states.

Before students can excel in advanced learning opportunities, they must be present. Thus we were encouraged to observe that eight states received As on participation measures. In fact, the only “A” measure grades received for excellence gap measures were in participation (Hawaii and Texas). In these states, we see the participation excellence gaps starting to close. These data may reflect recent efforts to increase representation of low-income students in gifted identification, advanced coursework, and AP courses. More work is needed to close participation gaps completely.

4. Although some states have impressive outcomes for their high-performing students, no state can claim impressive performance outcomes for students from low-income backgrounds.

States collectively earned higher grades than in the 2015 analysis on their excellence outcomes, with 14 states receiving Bs and 3 states receiving As. This may be due, in part, to a change in how we weighted AP results (i.e., 20 percent in 2015 vs. 33 percent in 2018). But overall advanced performance in several states appears to have increased at least slightly, suggesting progress.

However, any enthusiasm is quickly lost when excellence gap outcomes are considered. Only 1 state (Idaho) received a grade of B-, with all 49 remaining states and the District of Columbia receiving Cs and Ds. Readers should keep in mind that the excellence gap outcomes are even worse than they may appear, given that we graded the NAEP excellence gap data on a steep curve: To get full credit on those indicators, a state with 10 percent non-low-income students scoring advanced only needed 4.1 percent of low-income students to score advanced. Even with this low bar, only two states had small excellence gaps — Idaho and South Dakota on NAEP grade 8 Reading — and their small excellence gaps were due to low performance by non-low-income students, not improved performance by low-income students.

5. Universal screening is not common enough.

Recent research strongly supports universal screening whenever identifying students for interventions, given that other approaches to identification tend to under-identify even high-ability, low-income students.14 Although Colorado appears to be the only state with dedicated funding to support universal screening, several other states either require or encourage districts to use state funding for gifted education to support universal screening. The use of universal screening is widely considered to be the foundation of any efforts to eliminate excellence gaps, yet 42 states do not implement it. All states should seriously consider implementing comprehensive universal screening policies. We note that some states (such as Iowa) already mandate universal screening for learning difficulties; expanding that screening to identify advanced ability would be relatively easy and low cost.

6. Few states have a comprehensive talent development plan.

Few states appear to be taking a comprehensive approach to talent development, which largely explains the holes or “blind spots” in some states’ excellence and excellence gap policies. This is even true in states that are doing relatively well: they treat gifted education separately from Advanced Placement, which they address separately from dual enrollment and early graduation, which they see as distinct from school accountability issues. Approaching talent development in such a piecemeal, uncoordinated fashion leads to the patchwork policies that we witness in most states. Exceptions to that rule are states such as Alabama, Arizona, Colorado, and Minnesota, where state leaders and advocates work together to address excellence — and, to a lesser extent, excellence gaps — comprehensively. Yet even in these forward-thinking states, we do not see state-wide documents or other resources that outline how a talented child might receive a rigorous, advanced education from preschool through high school graduation.

7. States handle the use of local norms in very disparate ways.

Our final conclusion comes out of the conversations we had with state officials. Researchers are almost universal in their recommendation to use local norms when identifying children for advanced programming rather than national norms.15 In essence, local norms involve identifying a certain number or percentage of students in each school rather than identifying all of the students in a school that perform at a certain, predetermined level (e.g., the 95th percentile on a standardized test). Local norms generally produce a more diverse pool of talented students and are more likely to identify talented, low-income students.

However, local norms are often controversial in practice. One common concern is that, for example, a student identified using local norms in an impoverished, urban school could move to a wealthier suburban district, where they would presumably no longer qualify for services due to the higher local norms in the suburban district. Advocates for local norms often counter that the number of low-income students who move to wealthier districts is almost certainly greatly outweighed by the number of currently underserved, low-income students who would benefit from the use of local norms.

Research on this portability issue is largely nonexistent, and as a result, states have a range of policies regarding local norms. Some states prohibit or actively discourage use of local norms (such as the highest scoring policy state, Colorado), others require local norms but do not require portability (New Jersey), and others require local norms and portability (Mississippi). A careful analysis of the impacts of these various approaches to the use of local norms would greatly benefit policymakers and educators as they attempt to craft sound policies in this area.

Conclusions and Recommendations For States

Our federalist system of government places primary responsibility for education on individual states. Although the No Child Left Behind Act marked the height of federal intervention in K–12 education, recent years have seen the locus of control for schooling and students move firmly back to the states. This trend appears likely to continue over the next several years.

The return of education responsibility to the states and the District of Columbia means that related policies will differ, often substantially, across state lines. We observed these often stark differences when examining policies related to talent development and reducing excellence gaps. As a result, and not surprisingly, student participation and outcomes related to excellence and excellence gaps are quite variable among the states.

In contrast to the 2015 edition of this report, we found evidence that many states are paying attention to advanced achievement. Not all states, of course, but more than in 2015. Attention to shrinking excellence gaps is much less common.

The country needs to address excellence and equity comprehensively. The alternative — to accept the excellence gap as inevitable — is a recipe for long-term social and economic decline. Talent comes from all sectors of society — all races, all genders, and all income levels. More than half of the students enrolled in K–12 education in many states in this nation are low-income.16 As suggested by the evidence of the extraordinary support that better-resourced families can provide their children, ever fewer high-ability, low-income students are performing at advanced levels.17 If those two trends continue, it is reasonable to question how the United States will satisfy its insatiable need for talent. We are laying the groundwork for a persistent talent underclass. In the final analysis the problem is stark: if we fail to reduce the barriers to excellence for talent development of our brightest students, our economic preeminence will be fundamentally jeopardized.

Based on the results of this study, we provide six recommendations for states. To provide additional guidance to states, later this year the Cooke Foundation will release a report describing these recommendations in more detail and highlighting examples of promising practices.

States need to address excellence

and equity comprehensively. The

alternative — to accept the excellence

gap as inevitable — is a recipe for

long-term social and economic decline.

RECOMMENDATION 1:

Attend to both excellence and excellence gaps.

Interventions that increase overall academic excellence may not address excellence gaps. For this reason, we looked at excellence and excellence gap-focused policies separately, and we found sharp differences within and among states on the prevalence of these policies. In general, states appear to be slowly increasing their focus on academic excellence, but a focus on closing excellence gaps is not a priority in most states. This distinction is not semantic. For example, knowing that a state has a talent development mandate, identifies and serves large numbers of gifted students, and achieves high AP scores does not necessarily tell us anything about whether that state’s low-income students are excelling academically. States should treat the goals of promoting educational excellence and eliminating excellence gaps as related, but distinct, objectives.

RECOMMENDATION 2:

Maximize identification of students to receive advanced learning opportunities.

Students will never receive advanced instruction unless they are identified to do so. All states should require Local Education Agencies (LEAs) to identify advanced students through implementation of universal screening and use of local norms. Teacher preparation should include training on how to identify students who would benefit from increased rigor of instruction.

RECOMMENDATION 3:

Ensure that all high-ability students have access to advanced educational services.

States can and should take the lead in promoting educational excellence and eliminating excellence gaps. States should require services for gifted and talented students; require all educators to have exposure to the needs of advanced students in teacher, counselor, and administrator preparation coursework; and monitor and audit LEA gifted and talented programs for quality. In addition, states should provide for dual enrollment for high school students in college level coursework, by: partnering with local higher education institutions, providing AP courses, or facilitating dual enrollment in bricks-and-mortar and online college courses. And as researchers have noted, providing talent development opportunities with low barriers to entry is often not enough; low-income students and their caregivers may have to be convinced that the opportunities are worth pursuing.18

RECOMMENDATION 4:

Remove barriers that prevent high-ability students from moving through coursework at a pace that matches their achievement level.

Allowing high-ability students to move through the K–12 system at their own pace is one of the easiest and most straightforward interventions. State-level laws and policies should require LEAs to allow early entrance to kindergarten, acceleration between grades, dual enrollment in middle school and high school (with high school credit), and early graduation from high school.

RECOMMENDATION 5:

Hold LEAs accountable for the performance of high-ability students from all economic backgrounds.

Our analysis of state K–12 accountability systems was based on plans as they existed in 2016-2017. As we completed this study, states were beginning to offer their revised plans under the Every Student Succeeds Act, some of which are qualitatively different from their NCLB-era plans. Although we did not evaluate the new plans due to their draft nature, initial analyses of these plans are not positive from the perspective of promoting high achievement and addressing excellence gaps. The new plans should: give credit for advanced achievement; include high-achievers in growth assessments; separately report growth for high-achievers; and include other indicators of excellence. Other indicators currently captured by some states include: the number of students identified for gifted education; the college going rate; AP enrollment and performance; SAT and ACT performance; early entrance to Kindergarten; dual or concurrent enrollment; and early exit from high school. Accountability systems should also report separately low-income and other students to identify excellence gaps.

RECOMMENDATION 6:

Create a comprehensive talent development plan.

Because talent development has been a low priority for most states, relevant policies and programs almost universally have a patchwork feel: gifted education policies and interventions focus on mid-to-late elementary grades; middle school tends to be overlooked; AP policies are treated separately, as are dual enrollment policies. The lack of coordination among these moving parts leads to dysfunctional talent development systems that comprehensively address neither excellence nor excellence gaps. States should develop comprehensive P–16 plans for developing talent.19

About the Authors

Jonathan Plucker is the Julian C. Stanley Endowed Professor of Talent Development at Johns Hopkins University, where he works in the Center for Talented Youth and School of Education. His research examines education policy and talent development, with over 200 publications to his credit. Recent books include Excellence Gaps in Education with Scott Peters (Harvard Education Press), Critical Issues and Practices in Gifted Education with Carolyn Callahan (Prufrock Press), Intelligence 101 with Amber Esping (Springer), and Creativity and Innovation (Prufrock). His work defining and studying excellence gaps is part of a larger effort to reorient policymakers’ thinking about how best to promote success and high achievement for all children. He was the recipient of the 2012 Arnheim Award for Outstanding Achievement from the American Psychological Association and 2013 Distinguished Scholar Award from the National Association for Gifted Children. Professor Plucker is an AERA, APA, APS, and AAAS Fellow and has been ranked one of the Top 100 most influential academics in education for the past several years.

Jennifer Glynn is the Director of Research at the Jack Kent Cooke Foundation where she oversees the foundation’s evaluation and research efforts. Her recent reports include True Merit: Ensuring Our Brightest Students Have Access to Our Best Colleges with Richard Kahlenberg and Opening Doors: How Selective Colleges and Universities Are Expanding Access for High-Achieving, Low-Income Students. Her research examines college readiness, access, and success for students from diverse backgrounds. Prior to joining the foundation, Dr. Glynn led evaluations of nationwide federal and foundation-funded education programs as a senior associate at Abt Associates Inc., a social policy research firm headquartered in Boston, MA.

Grace Healey is a Research Assistant at the Johns Hopkins Center for Talented Youth. In addition to her research, she is a special education teacher who works with students with social and emotional disabilities at the Cooperative Educational Services (C.E.S.) Therapeutic Day Program in Connecticut.

Amanda Dettmer is a Research Associate at the Johns Hopkins Center for Talented Youth. In addition to this role, she is a behavioral neuroscientist who studies early life factors that contribute to sensitivity and resilience to chronic stress and associated cognitive, social, and behavioral outcomes. She also serves as the American Psychological Association’s Division 6 (Society for Behavioral Neuroscience and Comparative Psychology) representative to the Coalition for Psychology in Schools and Education (CPSE).

The Jack Kent Cooke Foundation is dedicated to advancing the education of exceptionally promising students who have financial need. Since 2000, the foundation has provided $175 million in scholarships to more than 2,300 students from 8th grade through graduate school, along with comprehensive counseling and other support services. The foundation has also awarded over $97 million in grants to organizations that serve such students. www.jkcf.org

Appendix A

DATA SOURCES

This report draws upon the following primary data sources. In addition, staff reviewed state education agency (SEA) web sites and data-bases, and conducted telephone interviews with staff members in state education offices to verify responses and obtain missing information.

2014–15 State of the States in Gifted Education.

Washington DC: National Association for Gifted Children (NAGC) and the Council of State Directors of Programs for the Gifted (CSDPG), 2015.

Website: http://www.nagc.org/resources-publications/giftedstate/2014-2015-state-states-gifted-education

High States for High Achievers in the Age of ESSA.

Washington DC: Thomas B. Fordham Institute, 2017.

Website: https://edexcellence.net/publications/high-stakes-forhigh-achievers-in-the-age-of-essa

The 10th Annual AP Report to the Nation.

College Board, 2014.

Website: http://media.collegeboard.com/digitalServices/pdf/ap/ rtn/10th-annual/10th-annual-ap-report-to-the-nation-singlepage.pdf

50-State Comparison.

Denver, CO: Education Commission of the States, 2017.

Website: http://ecs.force.com/mbdata/ MBQuestRTL?Rep=DE1501

State Acceleration Policy by State.

Acceleration Institute, 2014–15.

Website: http://www.accelerationinstitute.org/Resources/Policy/ By_State/

Digest of Education Statistics.

National Center for Education Statistics, 2015.

Website: https://nces.ed.gov/programs/digest/d15/tables/ dt15_204.90.asp?current=yes

Appendix B

STATE DATA TABLES

The following tables report the specific indicators for each state’s policies, participation measures, and outcomes. State values were rounded before scoring. Cells noted with an asterisk were not obtained through the primary data source, but through project staff research and/or phone calls to state officials.

Endnotes

1 Plucker, J. A., & Peters, S. J. (2016). Excellence gaps in education. Boston, MA: Harvard Education Press.

2 Plucker, J. A., Hardesty, J. & Burroughs, N. (2013) Talent on the Sidelines: Excellence Gaps and America’s Persistent Talent Underclass. http://webdev.education.uconn.edu/static/sites/ cepa/AG/excellence2013/Excellence-Gap-10-18-13_JP_ LK.pdf.

3 In Illinois, for example, the advocacy group One Chance Illinois led a research-directed initiative to pass new legislation (Bill SB2970) that would fund gifted education and mandatory identification screening in all schools.

4 See, for example, Axelrod, J., “Report: Inequality is making it harder to achieve American Dream”, CBS News, December 9, 2016. Hoover, E. and Carlson, S., “Students on the Margins”, The Chronicle of Higher Education, October 8, 2017.

5 Petrilli, M.J., Griffith, D., Wright, B. L., Kim, A. (2016) High Stakes for High Achievers in the Age of ESSA. Washington, DC: Thomas Fordham Institute. See also https://checkstateplans. org, and https://www.usnews.com/news/education-news/ articles/2017-06-27/education-plans-lack-clarity-ondisadvantaged-students-worst-schools

6 Members of the 2014-2015 expert advisory board included Prof. Carolyn Callahan (University of Virginia), Dr. Molly Chamberlin (Indiana Youth Institute), Peter Laing (Arizona Department of Education), Prof. Matthew McBee (East Tennessee State University), Prof. James Moore (Ohio State University), and Dr. Rena Subotnik (American Psychological Association). We gratefully appreciate their input, although all opinions expressed in this report are the responsibility of the authors.

7 We excluded one 2015 indicator from the current report, whether a state participates in international assessments, because only 9 states earlier had participated in international assessments in 2015 and none had participated in 2018. We added 13 new indicators based on new data found or collected.

8 Data sources included a report called the 2014-15 State of the States in Gifted Education, from the National Association for Gifted Children (NAGC) and the Council of State Directors of Programs for the Gifted (CSDPG), in addition to various reports provided by the College Board, Education Commission of the States (ECS), and state education agency (SEA) web sites and data bases.

9 We acknowledge that our methodology probably depresses the policy grades for states that attempt to address the needs of high-ability students specifically through the use of special schools. Although we intended to include such an indicator, we were not able to create a master list of special schools; furthermore, the use of special schools as an intervention model limits the number of students who can be served, making such schools an interesting piece of a comprehensive plan to support advanced learning but almost certainly not a highly effective stand-alone option.

10 Assouline, S., Colangelo, N., VanTassel-Baska, J., & Lupkowski-Shoplik, A. A Nation Empowered, Belin-Blank Center, University of Iowa: 2015.

11 Card, D. & Giuliano, L., “Universal screening increases the representation of low-income and minority students in gifted education,” PNAS vol. 113, no. 48, November 26, 2016, pp. 13678-13683.

12 We adjusted the scoring cut points down for grade 8 reading to reflect the overall lower levels of student achievement in this subject / grade level in the nation.

13 Neff, J and Doss Helms, A. (2017), “State, local leaders hope to fix exclusion of bright low-income students”, Raleigh News & Observer.

14 Hamilton, R., McCoach, D. B., Tutwiler, M. S., Siegle, D., Gubbins, E. J., Callahan, C. M., Brodersen, A., & Mun, R. U. (in press). Disentangling the roles of institutional and individual poverty in the identification of gifted students. Gifted Child Quarterly.

The Cooke Foundation is dedicated to advancing the

education of exceptionally promising students who have

financial need. Since 2000, the foundation has awarded

$175 million in scholarships to more than 2,300 students

from 8th grade through graduate school, along with

comprehensive counseling and other support services.

The foundation has also provided over $97 million in

grants to organizations that serve such students.