Jack Kent Cooke Foundation in the News: Forbes

We are so pleased to read about the Jack Kent Cooke Foundation in Forbes today, where several of our Scholars are featured. Print version should be on the newsstands within the week. Below is a preview found online at Forbes, which is written by Kerry Hannon.

Scholarships Aren’t Enough

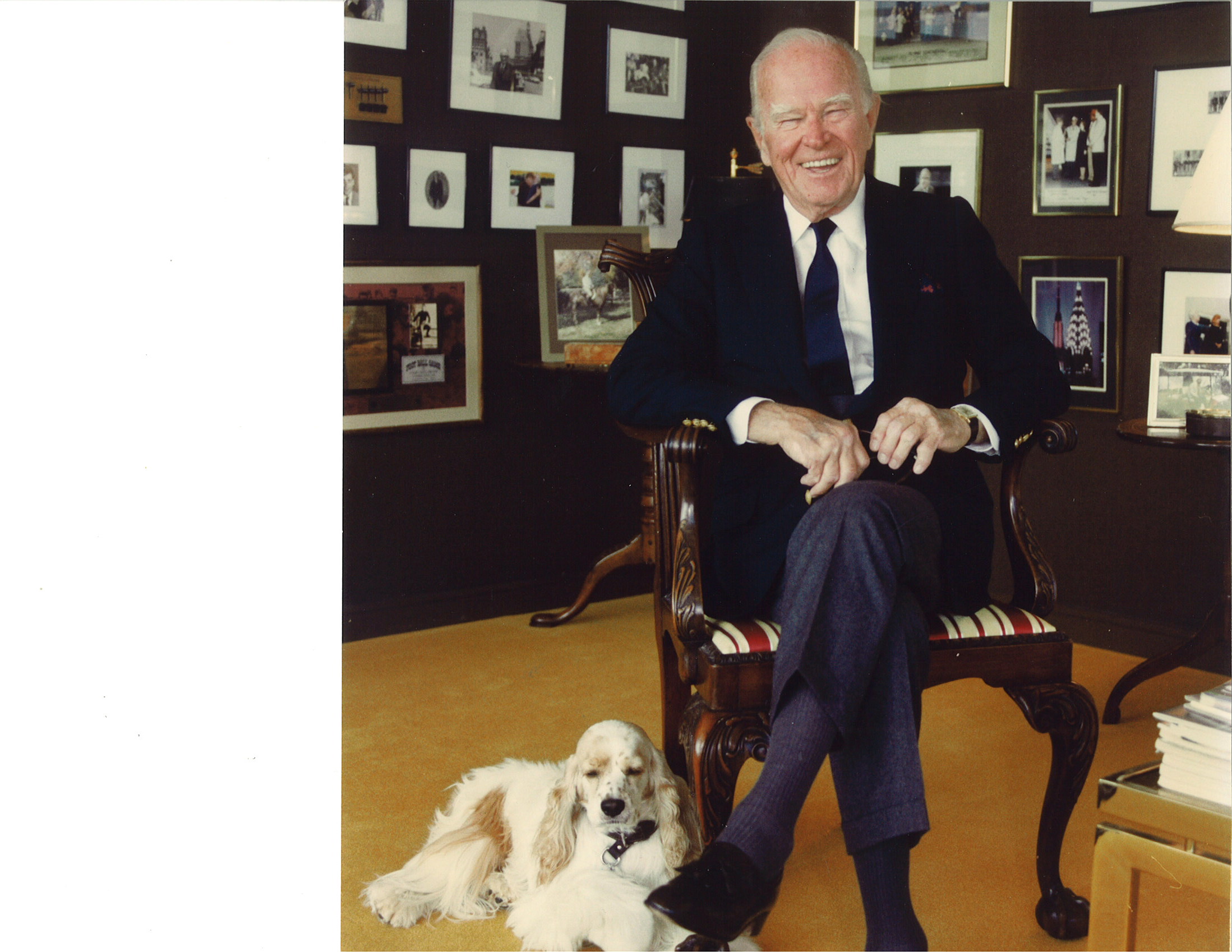

Jack Kent Cooke (Photo credit: Jack Kent Cooke Foundation)

One night, as they sat in his library sipping a $10 bottle of Meursault, Washington Redskins owner Jack Kent Cooke turned to Stuart A. Haney, his young lawyer and aide de camp, and declared: “Twenty years after I’m gone I will only be a footnote in the annals of the National Football League.”

But, as both men knew, Cooke wasn’t ready to settle for a footnote. A decade before his death in 1997 at age 84 he had secretly decided he wanted to be remembered for a namesake foundation devoted exclusively to helping a select group of brilliant, driven and in some cases musically gifted poor kids succeed.

Today, with $640 million in assets, the Jack Kent Cooke Foundation, based in Lansdowne, Va., offers some of the richest individual scholarships in the nation. Each year it picks about 60 eighth-grade “scholars” (average family income: $25,000) and provides them individual academic advisors, summer college and travel-abroad programs, laptops and, if need be, private school–in other words, the sort of enrichment lavished these days on kids from well-off families. Those extras continue through high school at an average cost of $15,000 per child a year. Any who continue to excel get college scholarships worth up to $30,000 a year, or another $120,000.

“Mr. Cooke didn’t want to do anything piecemeal,” Haney explains. “He said these kids are from very lean circumstances. Giving them $30,000 gets them in the door, but they aren’t going to stay there. We need to back them through the whole process, if possible.”

Some might question devoting so much money to a handful of kids who are already high achievers but not Nancy Green, executive director of the National Association for Gifted Children in Washington, D.C. “It’s about equity, not elitism,” she says. “They’re stepping in to support students with opportunities that are readily available to top students in the middle class and above.” With federal aid for poor children directed primarily toward those at risk of failing, helping the talented is a proper job for private money, she adds.

Cooke himself never even started college. Born in Canada in 1912 to middle-class parents, he was an indifferent student who cut class to hang out at a local music shop in Toronto where he taught himself to play piano and clarinet. After his dad went broke in the 1929 market crash, he left school with a lower-level high school diploma (it didn’t qualify him for college) and played at weddings and on Lake Ontario cruise ships with his band, Oley Kent and His Bourgeois Canadians. While he regretted not going to college, he also reportedly told friends that if he’d had more talent he would have made his living as a musician.

Instead, Cooke became a salesman, peddling encyclopedias and soap door-to-door. His big break came in 1936 when he landed a job running a radio station in Stratford, Ont., 100 miles from Toronto. The station was owned by budding media mogul Roy Thomson. Impressed by the younger man’s smooth salesmanship and drive, Thomson made him a partner. Cooke went on to earn a fortune from newspapers, radio stations and cable TV, moved to the U.S. in 1960 and appeared on The Forbes 400 list every year from its inception in 1982 until his death.

In contrast to Bill Gates, Warren Buffett and many of today’s 400 members, Cooke wasn’t a generous philanthropist during his lifetime. “He delighted in being a curmudgeon,” recalls Haney, who had the task of politely brushing off donation requests.

Rather than good works, Cooke was known for his sports teams and his four wives–the last two of them half his age. In 1979 he reached a $42 million divorce settlement with his first wife that made the Guinness Book of World Records as the largest to that date. To finance it he sold the NBA’s Los Angeles Lakers and NHL’s Los Angeles Kings to Jerry Buss, in what was the largest sports deal to that date. In 1987 he filed for divorce from his third wife after only 73 days, claiming the 31-year-old had gone back on a prenuptial agreement to terminate her pregnancy. (She later gave birth to a daughter.) In 1990 he got hitched to a woman headline writers dubbed the “Bolivian Bombshell”– she had done time in the federal pen for drug smuggling and, it turned out, wasn’t properly divorced from her previous husband. (Cooke had his marriage to the Bolivian annulled, then married her again after her previous marriage was properly dissolved.)

Meanwhile, as Haney tells it, on many a night Cooke would invite the young lawyer to his library where the two would drink cheap wine and hash over plans for the foundation. “It was Mr. Cooke’s relaxation after a difficult day to sit back and dream,” recalls Haney, now 56. He hoped that “some of the best minds in every single profession known to mankind” would become connected through his scholarships and foundation to form a sort of virtual think tank.

Yet even after Cooke’s will became public, melodrama and court battles overshadowed his charitable ambitions. The Bolivian, having been cut out of the will, sued and settled for millions. Cooke’s son, left just $50 million, fought desperately to keep the Redskins; other executors of the estate decided to sell the team, and he ultimately lost out to current owner Dan Snyder. The disappointed son then sued his fellow executors (including Haney) for charging excessive fees; a settlement reportedly cut their take by more than half to $17.5 million. Finally, the daughter Cooke never meant to have sued, too, claiming her $5 million trust had been mishandled and she couldn’t pay her college tuition. (She lost.)

Through it all, Cooke’s charitable plans survived. The foundation opened in 2000 and so far has spent $120 million on scholarships and direct support of students, while making $76 million in grants to other organizations helping gifted poor kids.

True to Cooke’s virtual think tank vision, recipients are brought to Virginia once a year for a weekend get-together, where they joke about being “Cookie cousins” with the same rich “Uncle Jack.” (On Cooke’s birthday, this past Oct. 25, some changed their Facebook profile pictures to one of Cooke.) During this year’s weekend meet-up, reps from 60 schools, including Amherst, Swarthmore and the University of California, Berkeley, showed up for the foundation’s annual college fair, conducting practice interviews and offering tips to the Cookies. The schools show up because they know the foundation has sloshed through a deep talent pool for them, choosing 60 from 2,000 applicants a year.

Identifying the most promising students so young “is tough because nobody is really accomplished at the age of 13,” admits Emily Froimson, vice president of programs at the Cooke Foundation. So the foundation relies heavily on standardized test scores and requires scholars to already be earning mostly As, with no Cs in core academic subjects. It also looks for accomplishments outside the classroom. “We want someone who will set goals for themselves, persistently works toward those goals and demonstrates resilience,” Froimson says.

When Harvard senior Edith Carolina Benavides heard she was a Cooke scholar, she cried and later translated the acceptance letter for her parents, who couldn’t read much English at that time. Benavides attended the local public high school in Mission, Tex., a few miles north of the Rio Grande . Meanwhile, Cooke prepared her for “the endless diversity present outside the Rio Grande Valley,” she says, by sending her to summer science programs at Smith, Brown and the University of Michigan. At 16 Benavides, who plays the sax, started an English and music tutoring program for children in Monterrey, Mexico. Now 21, she’s majoring in Romance languages and literature, still getting help from Cooke, and deciding between graduate school or working at a nonprofit.

Yasmine Arrington’s father has been in and out of prison since she was 3, and her mom died when she was almost 14, leaving a grandmother to raise Arrington and her two siblings. “Finances were always a huge problem for my family,” says the now 20-year-old junior at Elon University in North Carolina. A Cooke advisor helped her develop her interest in poetry; the foundation sent her to summer writing programs in New York State, North Carolina and Massachusetts as well as to a six-week summer study and community service program in Costa Rica. The foundation encourages scholars to do their own charitable works, and after years of hiding her own dad’s incarceration, in 2010 Arrington started ScholarCHIPS to raise money for scholarships for the children of prisoners.

So is Cooke simply helping those so talented and motivated they’d succeed regardless? Froimson insists not. “Kids may start off as high achieving but will fall out of the pipeline given a lack of resources and challenges,” she says. “It’s important for philanthropists not to forget this population. They are our future leaders, and we are wasting talent when we let these kids slip through the cracks.”

The foundation doesn’t, however, limit itself to finding the best and the brightest at 13. It also awards 40 four-year college scholarships, worth up to $30,000 a year, to high school seniors who weren’t in the early program; 75 two-year scholarships, also worth up to $30,000 a year, to poor kids who have aced community college; and a varying number of up to $50,000-a-year graduate scholarships to students who are studying music, art or creative writing.

On the college level the foundation fills gaps left after students have tapped other aid programs–gaps that scare some poor kids away and lead others to drop out. Most get federal Pell Grants, now as much as $5,645 a year, plus any need-based aid their college gives. Yet even at the handful of elite schools that claim to meet a student’s full financial need, Cooke’s support makes a difference. Typically a school’s financial aid package requires the student to spend ten hours or so a week earning money at a campus job; Cooke usually replaces those earnings with a grant, so the student can spend time doing an unpaid internship or research, as a child from a wealthier family might. If Cooke scholars take student loans (or if their parents take out Parent Plus loans to pay the “expected family contribution”), the foundation helps them repay those loans–provided they graduate with at least a B average.

One transfer scholarship recipient is Renata Martin, a junior biology major at Brown who wants to be an oncologist. She was born in Brazil and grew up in Kearny, N.J., where her dad delivers pizzas and her mom cleans houses. In high school, as an undocumented immigrant ineligible for federal aide, she worried she wouldn’t be able to go on to college. But she won a full merit scholarship from Essex County College, and during her second year there applied to 14 four-year schools and the Cooke Foundation. After she notified the schools that Cooke had awarded her $90,000 toward earning a B.A., the acceptances rolled in–from Brown, Johns Hopkins, Cornell and Georgetown, among others. She chose Brown, she says, in part for its liberal arts and creative community; in addition to medicine, she’s passionate about music. Martin plans to apply for an M.D./Ph.D. program beginning in 2015 and hopes to research cancer disparities in low-income communities.

Fitting in as a low-income transfer student at an Ivy League school can be tough, she notes, but her own self-confidence and the support provided by both the foundation and other Cooke recipients have made the transition work. “We call each other ‘Cookie cousins’ because we believe that our common struggles and dreams make us a family. And when you have a second family, things become much easier.”

How To Help

–Direct support. You can’t claim a charitable deduction for it, but you can pay anyone’s private high school or college bills directly (send the money to the school), plus give that person up to $14,000 a year for expenses, without worrying

about gift taxes.

–Existing organizations. If you’re looking to make a tax-deductible charitable contribution, consider the Children’s Scholarship Fund (which helps send kids to private school for K-8), the First Scholarship Fund (summer camp and college scholarships) or a school or local community scholarship fund.

–Endowing a scholarship. If you’re ready to donate at least $100,000, you can endow a scholarship specifically for low-income students through a community foundation or individual

This article is available online at:

http://www.forbes.com/sites/kerryhannon/2013/11/25/scholarships-arent-enough/